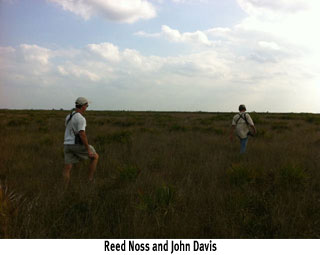

This post was contributed to Eco-Compass by Reed Noss, Provost's Distinguished Research Professor for the Department of Biology at University of Central Florida and author/editor of six Island Press books. Noss was a guest trekker with John Davis during TrekEast.

This past weekend, I had the wonderful opportunity to visit with my old friend John Davis—who is engaged in TrekEast—to show him one of my favorite places, Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park in south-central Florida. We met up with the park biologist, Paul Miller, and took a tour of the park for a day and a half.

Kissimmee Prairie contains the largest and most pristine expanse of an endangered ecosystem—the Florida dry prairie. This is an incredible place, with vast expanses of dry prairie, a natural community that contains the highest plant species richness of all treeless grasslands in North America, and one of the highest in the world. Other organisms, such as butterflies, are also extremely diverse here. The dry prairie once covered between one and two million acres, but has been reduced by some 90 percent, mostly by conversion to improved pastures. The signature species of the dry prairie is the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow, a federally Endangered subspecies that is completely restricted to this community and is probably the most imperiled bird in Florida, and one of the most imperiled on the continent. At the most, only a few hundred individuals remain and the population has been declining for reasons that are still unclear.

Federal and state agencies are not doing nearly enough to promote recovery of this species. I guess it’s hard for most people to get excited about a sparrow, but those of us who know it love this bird. It appears to be the most fire-dependent vertebrate in North America. After only three years without fire, its habitat becomes unsuitable and it cannot breed successfully.

The dry prairie is indeed dry this time of year, but is regularly inundated by a few inches of water in the summer wet season. We also visited some wetter habitats with John, including Gum Slough, which is the last known nesting location of the extinct Carolina Parakeet. The last confirmed nest was in 1927. Standing in the dwarf black gum–pop ash old-growth forest along the slough, one can imagine what is used to be like with flocks of Carolina Parakeets. Their ghosts were all around us.

The flat, seemingly monotonous Florida dry prairie landscape may not match the mountain splendor of some other regions of North America, but it has a charm of its own. There is nothing like it anywhere on earth and for the aware naturalist—no place is more spectacular.

Follow TrekEast on the blog and on Twitter.

The signature species of the dry prairie is the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow, a federally Endangered subspecies that is completely restricted to this community and is probably the most imperiled bird in Florida, and one of the most imperiled on the continent. At the most, only a few hundred individuals remain and the population has been declining for reasons that are still unclear.

Federal and state agencies are not doing nearly enough to promote recovery of this species. I guess it’s hard for most people to get excited about a sparrow, but those of us who know it love this bird. It appears to be the most fire-dependent vertebrate in North America. After only three years without fire, its habitat becomes unsuitable and it cannot breed successfully.

The dry prairie is indeed dry this time of year, but is regularly inundated by a few inches of water in the summer wet season. We also visited some wetter habitats with John, including Gum Slough, which is the last known nesting location of the extinct Carolina Parakeet. The last confirmed nest was in 1927. Standing in the dwarf black gum–pop ash old-growth forest along the slough, one can imagine what is used to be like with flocks of Carolina Parakeets. Their ghosts were all around us.

The flat, seemingly monotonous Florida dry prairie landscape may not match the mountain splendor of some other regions of North America, but it has a charm of its own. There is nothing like it anywhere on earth and for the aware naturalist—no place is more spectacular.

Follow TrekEast on the blog and on Twitter.

The signature species of the dry prairie is the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow, a federally Endangered subspecies that is completely restricted to this community and is probably the most imperiled bird in Florida, and one of the most imperiled on the continent. At the most, only a few hundred individuals remain and the population has been declining for reasons that are still unclear.

Federal and state agencies are not doing nearly enough to promote recovery of this species. I guess it’s hard for most people to get excited about a sparrow, but those of us who know it love this bird. It appears to be the most fire-dependent vertebrate in North America. After only three years without fire, its habitat becomes unsuitable and it cannot breed successfully.

The dry prairie is indeed dry this time of year, but is regularly inundated by a few inches of water in the summer wet season. We also visited some wetter habitats with John, including Gum Slough, which is the last known nesting location of the extinct Carolina Parakeet. The last confirmed nest was in 1927. Standing in the dwarf black gum–pop ash old-growth forest along the slough, one can imagine what is used to be like with flocks of Carolina Parakeets. Their ghosts were all around us.

The flat, seemingly monotonous Florida dry prairie landscape may not match the mountain splendor of some other regions of North America, but it has a charm of its own. There is nothing like it anywhere on earth and for the aware naturalist—no place is more spectacular.

Follow TrekEast on the blog and on Twitter.

The signature species of the dry prairie is the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow, a federally Endangered subspecies that is completely restricted to this community and is probably the most imperiled bird in Florida, and one of the most imperiled on the continent. At the most, only a few hundred individuals remain and the population has been declining for reasons that are still unclear.

Federal and state agencies are not doing nearly enough to promote recovery of this species. I guess it’s hard for most people to get excited about a sparrow, but those of us who know it love this bird. It appears to be the most fire-dependent vertebrate in North America. After only three years without fire, its habitat becomes unsuitable and it cannot breed successfully.

The dry prairie is indeed dry this time of year, but is regularly inundated by a few inches of water in the summer wet season. We also visited some wetter habitats with John, including Gum Slough, which is the last known nesting location of the extinct Carolina Parakeet. The last confirmed nest was in 1927. Standing in the dwarf black gum–pop ash old-growth forest along the slough, one can imagine what is used to be like with flocks of Carolina Parakeets. Their ghosts were all around us.

The flat, seemingly monotonous Florida dry prairie landscape may not match the mountain splendor of some other regions of North America, but it has a charm of its own. There is nothing like it anywhere on earth and for the aware naturalist—no place is more spectacular.

Follow TrekEast on the blog and on Twitter.