Parking Management for Smart Growth

256 pages

8.5 x 10

40 photos, 20 illustrations

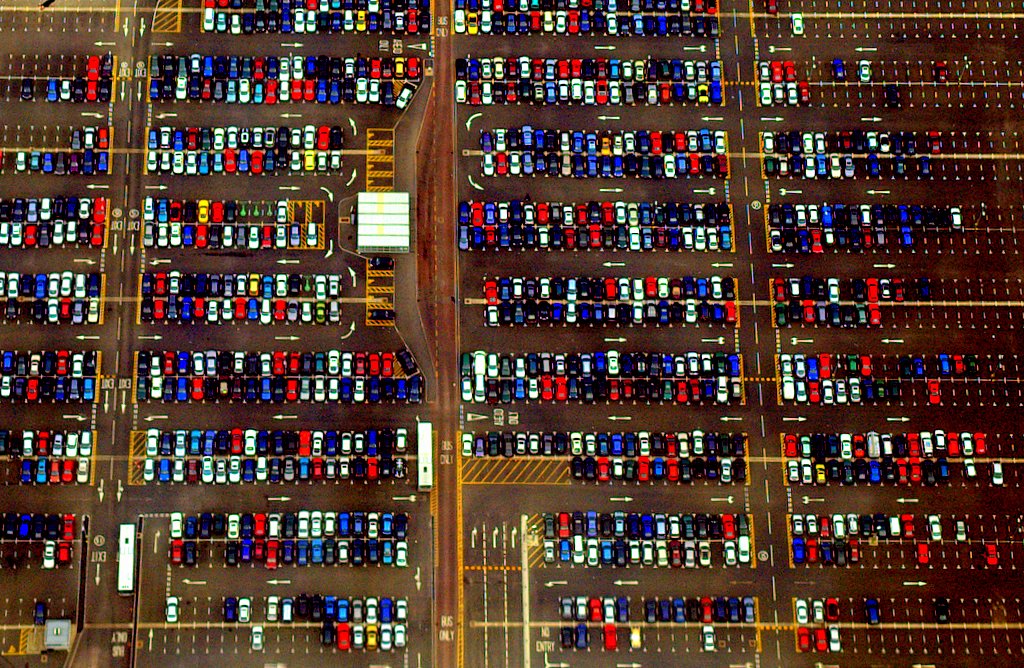

The average parking space requires approximately 300 square feet of asphalt. That’s the size of a studio apartment in New York or enough room to hold 10 bicycles. Space devoted to parking in growing urban and suburban areas is highly contested—not only from other uses from housing to parklets, but between drivers who feel entitled to easy access. Without parking management, parking is a free-for-all—a competitive sport—with arbitrary winners and losers. Historically drivers have been the overall winners in having free or low-cost parking, while an oversupply of parking has created a hostile environment for pedestrians.

In the last 50 years, parking management has grown from a minor aspect of local policy and regulation to a central position in the provision of transportation access. The higher densities, tight land supplies, mixed land uses, environmental and social concerns, and alternative transportation modes of Smart Growth demand a different approach—actively managed parking.

This book offers a set of tools and a method for strategic parking management so that communities can better use parking resources and avoid overbuilding parking. It explores new opportunities for making the most from every parking space in a sharing economy and taking advantage of new digital parking tools to increase user interaction and satisfaction. Examples are provided of successful approaches for parking management—from Pasadena to London. At its essence, the book provides a path forward for strategic parking management in a new era of tighter parking supplies.

"A quick reading of Parking Management for Smart Growth leaves even the casual reader with an overwhelming sense of the compelling logic for more rational parking policies to support better development….This book should be on the shelves of any planning department and local traffic department that has a parking problem, and probably those that do not."

Urban Land

"The book tackles the development of a parking management strategy, management of a parking district, best practices, and specifics on implementation. Only those in jurisdictions that are happy with empty acres of asphalt and all their implications can afford to skip this book."

Planning

"Parking Management for Smart Growth shows the potential and demonstrates the means for planners to implement active parking management...The book outlines a flexible roadmap for reform implementation and adaptation from which cities of all sizes can and should benefit."

Journal of Planning Education and Research

"Richard Willson has written a great book about how better parking management can improve transportation, the economy, and the environment. He clearly shows how cities can plan for smarter parking at lower cost instead of blindly spending other people’s money to get too much parking at far higher cost."

Donald Shoup, Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning, UCLA; author of "The High Cost of Free Parking "

"For cities, parking is destiny. While others have covered the theory of good parking management, Willson goes into the necessary details of implementation. He includes a wealth of case studies covering everything from effective use of technology, to addressing community concerns, to troubleshooting the problems that arise as theory moves into practice."

Jeffrey Tumlin, Nelson\Nygaard

"Taking new approaches to parking is integral to making cities more sustainable and more livable. Kudos to Richard Willson for bringing this important issue to light and for making the case that urban planners, policy makers, and city officials need to work with parking experts early in the planning process."

Shawn Conrad, CAE, Executive Director, International Parking Institute

Chapter 1. Introduction: What is a Parking Space Worth?

Parking as a Contested Space

Problems of Unmanaged Parking

Understanding Parking Behavior

Strategic Parking Management

Key Terms

Map of the Book

Chapter 2. Parking Management Techniques

Origins of Parking Management

Understanding and Organizing Parking Management Methods

Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced Parking Management

Parking Management Gone Wrong

Conclusion

Chapter 3. Creating a Parking Management Strategy

Planning and Strategy in Parking Management

Parking Management Stakeholders

Process for Developing a Parking Management Strategy

Process Pays

Chapter 4. Managing an Integrated Parking Supply (Rick Williams)

Management Principles

Organizational Structure: Administration and Management

Defining the Role of On-Street Parking

Relationship of On- and Off-Street Parking Assets

Rate Setting Policy and Protocols

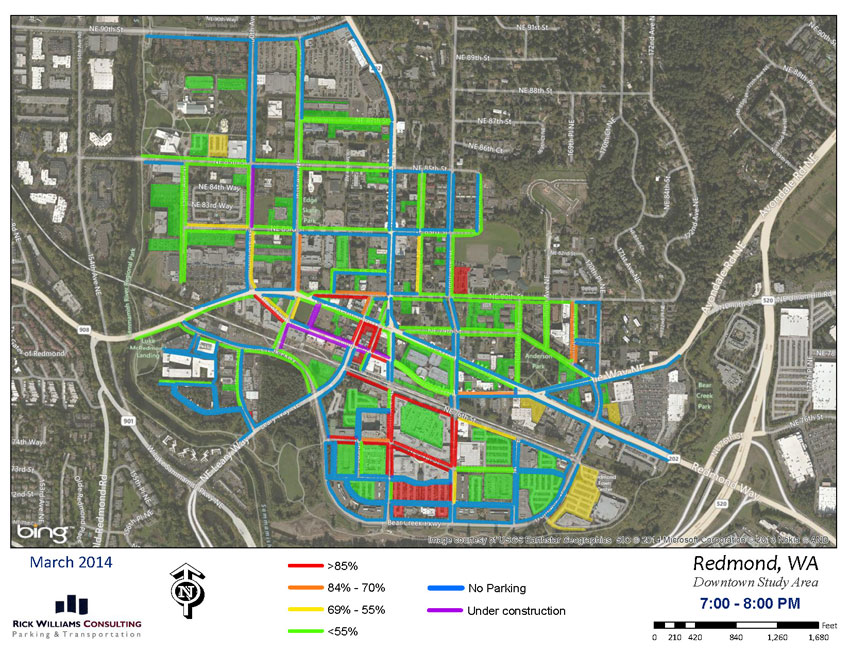

Measuring Performance

Identifying and Communicating the Integrated Parking System

New Technologies

Financial Analysis and Management

Conclusion

Chapter 5. Best Practice Strategies

Best Practice – Individual Measures

Best Practice – Integrated Strategies

Global Perspective

Case Study Conclusions

Chapter 6. Implementing Strategic Parking Management

Politics and Community Participation

Technical Challenges

Greening Parking Operations

Parking Enforcement

Conclusions on Implementation

Chapter 7. Parking Management for Smart Growth

A Paradigm Shift

Why Not Rely on Pricing Alone?

A Broader Vision for Strategic Parking Management

It’s Time

References

Index

The average parking space requires approximately 300 square feet of asphalt. That’s the size of a studio apartment in New York or enough room to hold 10 bicycles. In the last 50 years, parking management has grown from a minor aspect of local policy and regulation to a central position in the provision of transportation access. Join the UCLA Luskin Center and Lewis Center in welcoming Island Press author, Richard W. Willson, as he discusses his new book, Parking Management for Smart Growth, over refreshments and hors d’oeuvres.

Register to attend here.

Tuesday, April 5 at 8:00 am.

Join Parking Management for Smarth Growth author Richard Willson at the American Planning Association's National Conference for a session entitled "Your Next Step in Parking Management Discussion." You’ll learn about:

More details here.

Reforming minimum parking requirements is one of the most effective ways to support smart growth.

Join the Maryland Department of Planning and the Smart Growth Network at 1 p.m. Eastern, Tuesday, Aug. 4, as Richard W. Willson, Ph.D, FAICP, a professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Cal Poly Pomona, explains the problems created by the parking requirement status quo before presenting a step-by-step process for reforming minimum parking requirements. Willson will outline a toolkit that planners can use to provide an analytic and policy basis for parking requirement reform, offer examples of supportive parking management tools, and discuss strategies for moving reform forward with elected officials and stakeholders. Willson published Parking Reform Made Easy with Island Press in 2013.

Participants of the live webinar are eligible for 1.5 AICP CM credits. Register via the link below.

Photo by Ken Douglas, used under Creative Commons licensing.

Photo by Ken Douglas, used under Creative Commons licensing.

If you own a car, you've probably had to worry at one time or another about where you could park it. But these days between a place at your home, your office, your movie theater, and your favorite lunch spot, there are three parking spots for each car in America, and all that asphalt makes a real impact on planning and the feel of an urban environment. In Parking Management for Smart Growth, parking expert Richard W. Willson shows how towns and cities can use parking more strategically, making for more vibrant neighborhoods.

Last month, I gave a parking management presentation to a community group in Silver Lake, a neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles. They told me they had the worst parking problems in the city. If I had a penny for every time a community group told me that their parking problems are the worst ever, I would be wealthy.

Silver Lake’s parking conditions are typical of many revitalizing urban communities – more residents, buildings converted to higher intensity uses, older buildings with no off-street parking, more economic activity, and no vacant land for surface parking. In short, Silver Lake is the type of hip neighborhood that everybody wants. To check the community’s claims, my students conducted parking occupancy studies. They found that indeed, on-street parking occupancies were high.

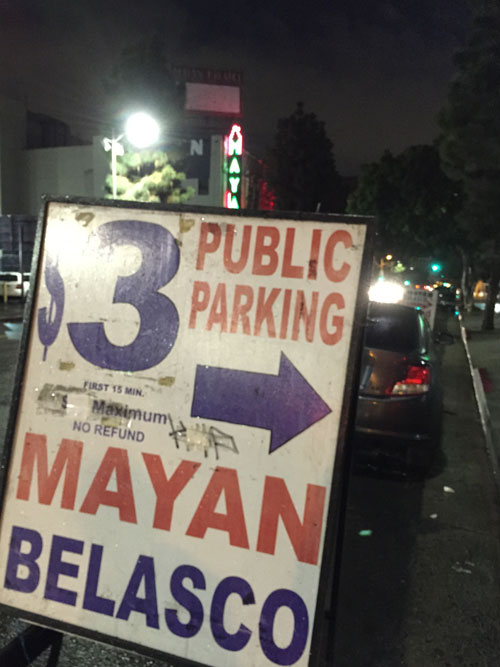

Silver Lake locals yearn for the old days of easier parking, but that would require reversing the economic vitality of the neighborhood and chasing residents out. There is no magic solution to parking, but existing parking resources can be more effectively managed to serve the community. Silver Lake already has LA Express Park variable meter pricing on Sunset Boulevard, the main commercial street. Many neighborhoods have residential permit programs with short-term commercial parking allowed during the day. So what else can be done? Here are some examples:

There is no way to return parking to how it was in the old days, when it was free and easily available. By managing parking in a way that is comprehensive (considering all parking resources) and coordinated, parking will be less chaotic, business activity can grow, and the community can prosper.

Why do so many good parking management ideas encounter resistance? For example, charging for curb parking is a no brainer. Priced spaces are used more times per day and better serve customers and visitors. Pricing encourages people to use less-known off-street spaces, reducing pressure to build expensive new parking facilities. Moreover, pricing provides revenue for local improvements. The most successful business districts charge for curb parking; the lagging ones do not.

I’ve engaged in hundreds of dialogues with officials and community members on parking charges. The resistance isn’t really about data or rationality – it’s cultural. Locals have a ‘small town’ image of their community. South Pasadena is one of those places – a city of 25,000 people in the heart of the largest county in the U.S. Drive down the streets of South Pasadena and you might think you are in a small town, but you are part of the 10 million residents of Los Angeles County. You participate in that economy and infrastructure system.

How does small town culture translate into parking? You park in front of the destination, for free. Local government requires that developers build lots of parking. Off-street parking is private, and so it isn’t shared with other uses. And curb parking in neighborhoods is “owned” by residents even though it is a public asset.

Big city parking is different. If you use a car, you park nearby your home or destination and walk, probably off-street. Parking costs money, sometimes a lot, and you decide on the tradeoff between price and walking distance. And because parking is worth something, there is an economic incentive for off-street parking owners to share it. A single space serves daytime retail customers, evening restaurant patrons, and overnight residents. That’s how parking works in downtown Los Angeles, a mere seven miles from South Pasadena.

There is a continuum between small town parking and big city parking. Where is your community on this continuum? What is the best way to nudge policy makers one step toward urban parking? South Pasadena, for example, should install meters on the popular curb spaces and leave free options elsewhere. Bigger cities should adjust parking pricing dynamically to ensure a few parking spaces are available on every block.

All the parking studies in the world won’t change minds if local culture drives perspectives. Here’s an approach forward. Create a discussion about broader community goals and show how parking management supports them. Make sure that all the voices are present – new business owners are more open to pricing than the old timers. Show decision makers examples of successful districts that use pricing and all the public improvements that result from the revenue. Just up the road from South Pasadena, Old Pasadena has shown the benefits of pricing for decades. Much as I would like to advance parking management with technical arguments, I’ve learned it demands dialogue, community by community. It takes the parking equivalent of a “horse whisperer”.

Since the beginning of time, parkers have argued that they should park free. Yet the economic justifications for pricing are well documented - pricing leads to more efficient parking use and a multimodal transportation system. Many arguments against pricing don’t hold up to scrutiny. I have been chronicling them in my work with local stakeholders over three decades. This blog post summarizes the top five arguments I’ve encountered and provides responses that are useful in the heat of the battle.

Convincing a person to change her or his mind is, of course, the greatest challenge of all. It has stumped teachers, marketers, philosophers, and religious leaders through the millennia. But is it possible, and it is more likely, when you understand the core ideas in the objections and frame the issue in a way that acknowledges them.

Religious institutions - churches, synagogues, mosques and other places of worship – are excellent prospects for shared parking. They need parking most on Saturdays or Sundays, in the morning, when there is lower overall parking occupancy. This post discusses two very different positions. The first is a progressive one that advances the church’s mission by selling off a church-owned parking lot and using shared parking resources. The second is a “protect our parking” approach common in disputes about parking, in which a church opposes bicycle lanes that would reduce on-street parking capacity.

Case #1. This is a positive parking management example from California. I recently helped the Board of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church assess the prospects for selling a surface parking lot it owns to a private developer for a mixed-use development. The sale included the condition that a small number of spaces in the new development are permanently allocated to the church, but the rest of the parishioner parking would be accommodated in the on-street and off-street parking in the Playhouse District. An analysis showed that there was plenty of parking capacity within walking distance of the church. The church is currently seeking city approval for a variance from the zoning code parking requirements. This arrangement converts an inefficiently used asset, a surface parking lot, into monetary resources that the church can use to augment its operations and advance its mission.

When it comes to approving shared parking, many cities are stuck in a counting game of seeking guarantees of shared parking access, requiring long-term agreements or covenants. This leads to complicated accounting that muddles property titles and makes parking owners wary of sharing. My view is that shared parking arrangements should be dynamic and changeable according to the circumstance of the entity needing the parking and the facilities providing it. Cities should rely on on-street parking prices to balance supply and demand, and to incentivize owners of off-street parking to share excess parking.

Case #2. The second case, the United House of Prayer in Washington, D.C., shows that organizations often fight for the status quo. They raise the convenience of parking in front of one’s destination to the level of a human right, or in this case, a constitutionally protected right. Long story short, the attorney for the church has claimed that replacing on-street parking with a bike lane in front of the church is a government action that “substantially burdens” the free exercise of religion. The controversy is impeding the development of innovative parking management ideas.

The District of Columbia is evaluating where to build a bike lane on the east side of downtown. The church’s representatives are arguing that a reduction in on-street parking brought about by the lane infringes on its “constitutionally protected rights of religious freedom and equal protection of the laws.” There is nothing in the constitution that creates a right to parking free in front of one’s desired destination. Some people may choose a church for the free parking, but that seems far from the more powerful explanation of finding a religious community that supports one’s personal growth and spirituality.

On-street parking is a public asset that should be used in the way that best serves the broader public interest. No one has a right to the on-street parking in front of a property s/he owns. But the “we own it” view is common, e.g., residential parking permit districts keep “outsiders” from parking in neighborhoods, and city governments rarely have the will to take on this notion. Acknowledging this political reality, a promising strategy is to price the use of on-street parking and return a portion of the revenues to the neighborhood for sidewalk repairs, street tree trimming, shared parking facilities, or other local priorities. That way, neighborhoods have an incentive to share their parking.

No one likes change, and I understand why the United House of Prayer is concerned. But opposing a bicycle lane would hold back progress in developing a multimodal transportation system. There are a host of way to get parishioners to church, including shared parking with nearby institutional or commercial uses, remote parking with shuttle busses, church busses, valet parking, time-specific conversion of travel lanes to parking, carpooling programs, taxi programs, and so on. It takes some effort but shared parking is a better approach than blocking the bicycle lane.

Last week, President Obama had this to say about the future of transportation at his final State of the Union Address: “Rather than subsidize the past, we should invest in the future — especially in communities that rely on fossil fuels. That’s why I’m going to push to change the way we manage our oil and coal resources, so that they better reflect the costs they impose on taxpayers and our planet. That way, we put money back into those communities and put tens of thousands of Americans to work building a 21st century transportation system.”

We wanted to know—what will this 21st century transportation system look like? We turned to some of our authors to find out:

Ray Tomalty, co-author of America's Urban Future (forthcoming February 2016)

The president was of course alluding to a carbon tax, which he is known to favor over cap-and-trade systems. Economists estimate a carbon tax could raise $1.2 to $1.5 trillion per year in the US, and if even a small part of this were spent on developing innovative transportation technology, a 21st century transportation system would be a real possibility in the US. At present, only about $2.3 billion in federal spending is devoted to transportation research. This is helping to test new technologies such as vehicle-to-vehicle communication, which has great potential to avoid accidents and improve traffic flow, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve travel times, and obviate the need for road infrastructure expansion. This technology is being tested on small stretches of urban highways across the country, but at the present rate of investment, it will be decades before fully automative vehicles are widespread in the US.

Many transportation experts believe the most pressing application of driverless technology is in driverless buses, which can greatly reduce the cost of public transit and vastly improve service. Unfortunately, little research and development is being dedicated to this purpose, something that could be addressed with funding from a carbon tax. Drone technology is another research and development area in need of greater public investment, a technology that is bringing the driverless movement to aviation and creating new possibilities for personal and goods transportation. Beyond research, new investment is needed in innovative transportation infrastructure. High-speed train service is a proven technology all over the developed world but in its infancy in the US (only one high-speed route in the country, the Acela Express linking Boston to Washington).

More thinking and research is also needed to explore the link between new transportation technologies, behavioral responses, and land use planning. This will require greater cooperation among local, regional and state planning authorities and cross-sectional cooperation among planning and transportation agencies. As the soon-to-be-released book, America’s Urban Future, written by Alan Mallach and myself shows, this is a field in which Canadian metropolitan areas have a long history of experimentation, so there may be something to be learned by looking north of the border for ideas on moving forward on this front.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock

Grady Gammage, author of The Future of the Suburban City (forthcoming April 2016)

By about 2050, driving your own vehicle will be a recreational activity like off-road four wheeling. Routine travel in autonomous, mostly electric vehicles will be commonplace. The cars will be smaller, lighter and often shared use but mostly they will still have only one or two people in them at a time. Transit in all forms will dramatically increase, but in most cities people will still be living in houses with driveways and garages and they’ll use personal mobility vehicles to get around.

Carlton Reid, author of Roads Were Not Built for Cars

Cars? Where we’re going we won’t need cars. The past can tell us a lot about the future, and the past tells us that we’re very poor at predicting the next transport revolution.

18th-century folk thought canals would last forever. Early 19th-century folk thought the same about turnpike roads. And for those who grew up in the "railway age," the only future imagined was of steel rails and steam trains. Few predicted the motor car’s eventual dominance, and it’s reasonable to assume that the same inability to accurately predict the future afflicts us, too. As "car age" people, we tend to extrapolate into the future of transport using what we know, and that’s car-shaped objects on roads. The Tesla is a wonderful thing but the technology that underpins it is hardly new – electric cars were more popular in the 1890s than gasoline cars. And electric cars may appear to be “cleaner,” but this is only true if they’re replenished by solar power – all other recharging methods involve traditional power sources so, really, most electric cars are coal-powered cars.

And what of autonomous cars? Again, this is hardly the disruptive technology that many think it is. I’ve been using driverless cars for 50 years, cars which scuttle away and hide when not needed. Taxis. I can summon one with an app when in a meeting and it will appear outside and whisk me to wherever I want to go. When I use taxis, including Uber, I can kick back and let the driver – a silent automaton if I so will it – worry about the road ahead. I fiddle on my smartphone without even raising my eyes. Where autonomous vehicles might change the world – if we let them, and I’d rather we didn't – is over who has priority on roads. Currently, driverless cars are programmed to avoid cyclists and pedestrians. In a city full of cars driven by onboard computers it will be a great game to ride or step in front of them, safe in the knowledge they’re programmed not to touch you.

Because cities are expected to fill with more and more people I don’t see how driverless cars will be able to navigate around these empowered pedestrians or emboldened bicyclists, at least not in central business districts. It’s far more likely that there’s another technology waiting in the wings that we can scarcely even imagine. That is certainly what happened to our forebears. Until then (and, if I’m allowed to, even after then) I’ll continue to ride my bicycle. A driverless car has clear user benefits, but an autonomous bicycle would be rather dull and pointless.

Richard Willson, author of Parking Management for Smart Growth

Just as we need to stop subsidizing the past in energy policy, we need to stop subsidizing the past by favoring driving and parking over more appropriate transportation modes. Parking should be priced to cover both its actual cost and the costs it imposes on others and the planet. This is rarely the case in US cities, where the dual legacies of excessive minimum parking requirements and parking subsidies have distorted vehicle ownership and travel choices. These distortions have in turn, undermined land use efficiency, design, social equity, and livability. The 21st century transportation system will have fewer privately-owned cars and less parking. New technologies will ensure that we have all the mobility we want with fewer cars. Car companies know this – that’s why they are redefining themselves as mobility companies.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock

Jeffrey Kenworthy, co-author of The End of Automobile Dependence

New technologies will clearly be part of any 21st century transportation system, including autonomous cars, but they should not be embraced in the way they are currently envisaged. A car is a car and takes up space with roads and parking, as well as helping to facilitate the continued destruction of agricultural land and natural areas through sprawl. This can be said of autonomous cars as well as electric cars, so ideally a 21st century transportation system will not look like the current automobile-dependent system in the USA, where cars are still responsible for around 96% of all the motorized passenger travel in cities.

A 21st century urban transportation system will have a multitude of modes (walking, bikes, car-sharing, transit, car-on-demand, private cars and probably other innovative technologies such as pedelecs, Yikes, etc.) seamlessly linked together. This will be achieved increasingly through the use of smart communications technologies, which will give people instant access via smart phones and tablet computers, for the best combination of modes for any trip.

In all the excitement over autonomous cars, we must not forget that electrically powered conventional transit modes such as light rail (LRT) and metro systems are still vastly under-provided for in US cities, due to being starved of adequate funding over the last 80 years. With advances in design, materials, comfort, on-board facilities, wireless networks and many other improvements, especially more protected rights-of-way, using transit in the future will be very different from what we know today. 21st century transportation systems should not only see more transit, but much more non-motorised movement, such as walking and cycling, leading to a less obese nation. This change alone will see billions shaved off US health care costs, not to mention the cost savings of a "road diet.”

John Renne, co-author of Transport Beyond Oil

Rapid changes in technology, such as self-driving electric cars and trucks, hold promise that the transportation industry will continue to innovate during the 21st century. Combined with a societal move towards an information and sharing-economy there is no doubt that marginal efficiencies will allow for a less carbon-intensive transportation system. However, the scale and intensity of weather impacts due to climate change necessitate a more drastic approach to achieve the key goal of limiting global temperature rise. The good news is that the path is simple. Anything we can do to promote walkable and bikeable communities will have the greatest impact. Therefore, we need to prioritize mass transit, which is the only transportation technology that has been proven to create walkable communities at the local level and deliver regional connectivity with the lowest consumption on carbon and emissions.

We’re saddened to learn of the untimely passing of Island Press author Richard Willson. He was a kind person who was fiercely dedicated to creating better cities. Rick’s enthusiasm for regulatory reform, and his optimism for the ability of planners to change the world were an inspiration to many. His views were evident in the original subtitle he suggested for his guide for idealists: “change the world and grow your character”. He will be missed.

In celebration of Rick's life, take a moment to read Chapter 1. What is a Parking Space Worth?, from his important book, Parking Management for Smart Growth.

Download it here or read it below.