Can a City Be Sustainable? (State of the World)

448 pages

6.5 x 8.38

35 photos, 35 illustrations

448 pages

6.5 x 8.38

35 photos, 35 illustrations

Cities are the world’s future. Today, more than half of the global population—3.7 billion people—are urban dwellers, and that number is expected to double by 2050. There is no question that cities are growing; the only debate is over how they will grow. Will we invest in the physical and social infrastructure necessary for livable, equitable, and sustainable cities? In the latest edition of State of the World, the flagship publication of the Worldwatch Institute, experts from around the globe examine the core principles of sustainable urbanism and profile cities that are putting them into practice.

State of the World first puts our current moment in context, tracing cities in the arc of human history. It also examines the basic structural elements of every city: materials and fuels; people and economics; and biodiversity. In part two, professionals working on some of the world’s most inventive urban sustainability projects share their first-hand experience. Success stories come from places as diverse as Ahmedabad, India; Freiburg, Germany; and Shanghai, China. In many cases, local people are acting to improve their cities, even when national efforts are stalled. Parts three and four examine cross-cutting issues that affect the success of all cities. Topics range from the nitty-gritty of handling waste and developing public transportation to civic participation and navigating dysfunctional government.

Throughout, readers discover the most pressing challenges facing communities and the most promising solutions currently being developed. The result is a snapshot of cities today and a vision for global urban sustainability tomorrow.

"What is embraced throughout the pages...is our future: not a doom and gloom snapshot of terrible things to come, but a positive look toward what we, as a species, can accomplish if we work at it. Can a City Be Sustainable? brings exciting ideas to our attention in an accessible way...[it] does exactly what it sets out to in its first sentence: give us hope."

Spacing

"Provides an excellent coverage of urban sustainability, establishing the necessary linkages between the urban climate challenges and the other, equally problematic, environmental excesses of urban civilization...[The book] is undoubtedly a solid contribution and bound to be a reference for some years to come."

Journal of Planning Education and Research

"informed and informative"

Midwest Book Review

Acknowledgments

Foreword \ Garrett Fitzgerald

Foreword \ Eduardo Paes

World's Cities at a Glance \ Gary Gardner

Part I. Cities as Human Constructs

Chapter 1. Imagining a Sustainable City \ Gary Gardner

Chapter 2. Cities in the Arc of Human History: A Materials Perspective \ Gary Gardner

Chapter 3. The City: A System of Systems \ Gary Gardner

Chapter 4. Toward a Vision of Sustainable Cities \ Gary Gardner

Chapter 5. The Energy Wildcard: Possible Energy Constraints to Further Urbanization \ Richard Heinberg

Part II. The Urban Climate Challenge

Chapter 6. Cities and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: The Scope of the Challenge \ Tom Prugh and Michael Renner

Chapter 7. Urbanism and Global Sprawl \ Peter Calthorpe

-City View: Shanghai, China \ Haibing Ma

Chapter 8. Reducing the Environmental Footprint of Buildings \ Michael Renner

-City View: Freiberg, Germany \ Simone Ariane Pflaum

Chapter 9. Energy Efficiency in Buildings: A Crisis of Opportunity \ Gregory H. Kats

-City View: Melbourne, Australia \ Robert Doyle

Chapter 10. Is 100 Percent Renewable Energy in Cities Possible? \ Betsy Agar and Michael Renner

-City View: Vancouver, Canada \ Gregor Robertson

Chapter 11. Supporting Sustainable Transportation \ Michael Renner

Chapter 12. Urban Transport and Climate Change \ Cornie Huizenga, Karl Peet, and Sudhir Gota

-City View: Singapore \ Geoffrey Davison and Ang Wei Ping

Chapter 13. Source Reduction and Recycling of Waste \ Michael Renner

-City View: Ahmedabad and Pune, India \ Kartikeya Sarabhai, Madhavi Joshi, and Sanskriti Menon

Chapter 14. Solid Waste and Climate Change \ Perinaz Bhada-Tata and Daniel Hoornweg

-City View: Barcelona, Spain \ Marti Boada Junca, Roser Maneja Zaragoza, and Pablo Knobel Guelar

Chapter 15. Rural-Urban Migration, Lifestyles, and Deforestation \ Tom Prugh

Part III. Politics, Equity, and Livability

Chapter 16. Remunicipalization, the Low-Carbon Transition, and Energy Democracy \ Andrew Cumbers

-City View: Portland, Oregon, United States \ Brian Holland and Juan Wei

Chapter 17. The Vital Role of Biodiversity in Urban Sustainability \ Marti Boada Junca, Roser Maneja Zaragoza, and Pablo Knobel Guelar

-City View: Jerusalem, Israel \ Marti Boada Junca, Roser Maneja Zaragoza, and Pablo Knobel Guelar

Chapter 18. The Inclusive City: Urban Planning for Diversity and Social Cohesion \ Franziska Schreiber and Alexander Carius

-City View: Durban, South Africa \ Debra Roberts and Sean O'Donoghue

Chapter 19. Urbanization, Inclusion, and Social Justice \ Jim Jarvie and Richard Friend

Notes

Index

Please join the Worldwatch Institute for the release of State of the World 2016: Can a City be Sustainable? on Tuesday, May 10, 2016 from 1:00-5:00 pm in Washington, D.C. Reception to follow. Can't make it? Register for the live webcast instead.

Cities are the world’s future. Today, more than half of the global population—3.7 billion people—are urban dwellers and that number is expected to double by 2050. There is no question cities are growing; the only debate is over how they will grow. Will we invest in the physical and social infrastructure necessary for livable, equitable, and sustainable cities?

In the latest edition of State of the World, experts from around the globe examine the core principles of sustainable urbanism and profile cities that are putting them into practice. We first put our current moment in context, tracing cities in the arc of human history, and examine the basic structural elements of every city: materials and fuels, people and economics, and biodiversity.

More details about the in-person event here and the webcast here.

This blog originally appeared on the Worldwatch Institute's blog and is reposted with permission.

Cities are the world’s future. Today, more than half of the global population—3.7 billion people—are urban dwellers and that number is expected to double by 2050. There is no question cities are growing; the only debate is over how they will grow. Will we invest in the physical and social infrastructure necessary for livable, equitable, and sustainable cities? Follow the Worldwatch Institute as we prepare for the May 10, 2016 release of State of the World: Can a City Be Sustainable?

--

As increasing numbers of people squeeze into cities, where can urban communities grow green spaces?

The world’s expanding cities are in a delicate balancing act. If they do not embrace strategic, high-density development, urban areas will increasingly encroach on surrounding farmland and natural spaces. This, in turn, creates the need for additional energy and transit infrastructure and widens their climate impacts. But if cities develop without green or open spaces, urban residents risk suffering from health problems, deteriorating social cohesion, and the loss of economic opportunities as the appeal of urban life fades.

Luckily, landscape architects and urban planners are finding innovative solutions to pack more green spaces within city boundaries, without pushing out existing living and working spaces. Below are five examples of stunning parks that incorporate green spaces into the fabric of urban life.

Blight to Beauty

The Atlanta BeltLine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Rendering of the Atlanta BeltLine (Ryan Gravel).

The splashpad at Historic Fourth Ward Park. Left photo: Christopher T. Martin. Right photo: Atlanta BeltLine, Inc

The Atlanta BeltLine is a prime example of “upcycling” underutilized urban space. Initially a hypothetical thesis project by a student at Georgia Tech in 1999, the project has become one of the largest urban redevelopment programs in the United States. It boasts a planned 520 hectares (1,300 acres) of new parkland—that’s more than the 340 hectares (840 acres) of New York City’s Central Park. Add the 400 hectares (1,000 acres) of remediated brown fields and 5,600 units of affordable housing, and the scale of the project becomes clear. The BeltLine rings the center of Atlanta using an existing 35-kilometer (22-mile) rail corridor that fell into disuse when the city grew beyond its initial boundaries. Today, the rail line links 45 neighborhoods, providing both transportation corridors and public space complete with an arboretum and spaces for fitness, play, art, and special events.

The Lowline, New York City, United States

Rendering of the Lowline.

The Lowline Lab before installation (Brandt Graves). The existing Lowline Lab.

Like its New York City cousin the High Line, the Lowline takes advantage of neglected transit routes to add a vertical dimension to public green spaces. Although it is still in its concept phase, the Lowline proposes an innovative design in an abandoned trolley terminal. What makes this project so intriguing is its use of passive solar technology to illuminate the space and provide light to plants and people below street level. A solar reflector dish guides sunlight from above to an underground dome that scatters the light.

Prioritizing People Over Cars

Madrid Río, Madrid, Spain

Rendering of Madrid Río (CityLife).

Madrid Río in 2004 and 2011, before and after burying the highways.

After a massive highway was built on both sides of the Manzanares River in Madrid in the 1970s, nearby neighborhoods declined and most Madrileños avoided the region entirely. In 2003, however, Mayor Alberto Ruíz-Gallardón implemented his vision to bury the highways and move traffic through tunnels instead (not without great political pushback). Ultimately, however, the river banks were freed for pedestrians and more than nine kilometers (six miles) of the Madrid Río Park were designed with playgrounds, ball fields, bike paths, and a wading pool known fondly as “the beach.”

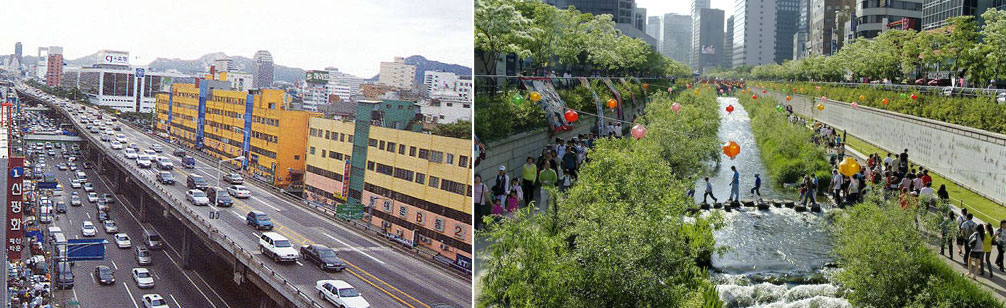

Cheonggyecheo, Seoul, South Korea

Cheonggyecheo Stream Park (Kimmo Räisänen).

Cheonggyecheo Stream before and after highway removal (Intermediate Landscapes).

Peeling back the 5 kilometers (three miles) of elevated highway that covered the once-polluted Cheonggyecheon Stream has turned a congested area in Seoul into a green haven for picnickers and pedestrians. While the park is far from perfect in its environmental design (water is pumped through 11 kilometers, or seven miles, of pipes from the Han River to feed the stream), some wildlife has returned, pollution has decreased, property values have gone up, and some 90,000 people visit daily. Combined with expanded bus service, higher parking fees, and restrictions on cars, nearby congestion has gone down and reduced small-particle air pollution along the corridor. The area also experiences lower local temperatures compared to those of nearby areas, a boon as climate change extremes are likely to increase in frequency.

Continue reading the full post here.

This post was originally published on Worldwatch.org and has been posted here with permission.

How are urban social issues shifting?

Jarvie & Friend: With cities recognized as being at the forefront of addressing global climate change, it is clear that urbanization of the future will need to be very different from urbanization of the past, and from current trajectories. There is an urgent need for a transformative urban future that is socially just, inclusive, and ecologically viable.

The biggest challenge to this transformative urban agenda is improving governance to achieve sustainability goals in places where it currently is dysfunctional, corrupt, inefficient, and/or incompetent, even though all required policies and regulations are nominally present. A greater focus on rights-based approaches needs to facilitate processes through which desperately needed city investments can be made in inclusive, transparent, and accountable terms. Until social gaps are closed, inequity will rise both within and among cities.

“As urbanization increasingly leaves the poor behind, the international community is starting to pay attention.”

—James Jarvie and Richard Friend in “Chapter 19: Urbanization, Inclusion, and Social Justice”

What does city structure have to do with sustainability?

Schreiber & Carius: Cities are not only growing in population, but also becoming increasingly diverse and ethnically heterogeneous. Socioeconomic polarization and spatial segregation have become prevailing trends in cities worldwide, with adverse impacts on quality of life and social cohesion.

Although urban planners and designers cannot solve the roots of exclusion and inequality per se, they can aid in increasing the accessibility and integration of deprived areas and provide spaces that increase the chances of interaction and the forming of social relations among people from differing ethnic backgrounds. The creation of mixed-use and socially mixed areas—coupled with good access to public transport, housing diversity, and sufficient provision of vibrant public spaces that facilitate inter-ethnic encounters—are promising ways to enhance social cohesion.

“Finding solutions to counteract disparities and inequalities while strengthening relations and interactions among socially and ethnically diverse groups has become an urgent matter.”

—Franziska Schreiber and Alexander Carius in “Chapter 18: The Inclusive City: Urban Planning for Diversity and Social Cohesion”

What does transportation have to do with sustainability?

Renner: Transportation—the movement of people and goods—is the lifeblood of a city. Inadequate transport systems constrain a city’s economy and vitality. But making a city too dependent on motorized transport can cause a host of other problems: traffic jams and deadly accidents, debilitating air pollution, and the loss of valuable land to streets, highways, and parking lots.

Car- and truck-centered transportation systems run the risk of becoming like clogged arteries: they are bad not only for the vitality and attractiveness of cities, but also for urban residents’ health, local environmental quality, and the global climate. As experience worldwide shows, wide-ranging options are available to cities wanting to reduce the footprint of their transportation systems. The opportunities are matched by the urgency with which cities everywhere need to act.

“To become sustainable, cities need to sharply reduce reliance on automobiles and to work to ensure a better mix of well-integrated transportation modes.”

—Michael Renner in “Chapter 11: Supporting Sustainable Transportation”

Calthorpe: Mixed-use, walkable, economically integrated, and transit-rich places define good urbanism. More often than not, the positive outcomes that result cost less in upfront infrastructure, ongoing maintenance, and the average household cost of living. Cities that persist in low-density development that isolates activities and income groups and has poor transit will heighten economic and social ills as well as emit more carbon.

The developing world needs massive quantities of affordable high-capacity transit. The developed world needs land uses and transit features that are good enough to move people who are rich enough to have a choice out of their cars. How can this change be accomplished? For developing economies, it is an issue of capacity. For China and the developed world, shifting metropolitan forms toward better outcomes is an issue of political will.

“If cities fail and become matrixes of gridlock, poisonous air, economic segregation, and environmental pollution, the planet will follow.”

—Peter Calthorpe in “Chapter 7: Urbanism and Global Sprawl”

The responses above are excerpted from chapters by contributing authors in Can a City Be Sustainable?, a State of the World report.

This post originally appeared on Worldwatch.org and has been published here with permission.

Can cities shift their systems and structures to become sustainable? This is the first of two exclusive sneak peeks into our newest State of the World publication, Can a City Be Sustainable?. Here we feature perspectives from five chapter authors: Richard Heinberg, Betsy Agar & Michael Renner, Gregory Kats, and Andrew Cumbers.

What could changes in energy supply mean for cities?

Heinberg: Ongoing urbanization means that societies need to keep providing more goods to growing ranks of city dwellers. Urban provisions require energy. But our current fossil fuel-based energy regime faces two serious challenges: depletion of the “low-hanging fruit” of global petroleum supplies, and the need to reduce carbon emissions to avert catastrophic climate change.

Energy challenges may result in systems that are more expensive to operate than current ones or that simply fail to deliver all the services that we currently expect. Such challenges could cause the current trend toward urbanization to taper off or even reverse itself. It is impossible to know how close we may be to that tipping point, but it could well occur during this century, and a decline in available energy is likely to be the key driving factor.

“It is possible to imagine a non-catastrophic pathway to de-urbanization. For optimum success, however, it almost certainly would need to be guided by sound policy.”

—Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow-in-Residence at the Post Carbon Institute, in “Chapter 5: The Energy Wildcard: Possible Energy Constraints to Further Urbanization”

Is 100 percent renewable energy in cities really feasible?

Agar and Renner: Committing to 100 percent renewable energy means significantly more than flipping a few switches. It requires making strong commitments to energy efficiency as well as to renewables in the three major urban energy-use sectors: electricity, heating and cooling, and transportation. Beyond these sectors, the commitment drives social change, animates a diversity of actors, demands innovative policies, transforms economies, and develops knowledge and skill capacities.

Around the world, many cities are taking steps to put their energy supplies on a more sustainable footing. Now, more than ever, cities have the planning tools, financial incentives, technical know-how, and public support to transition to 100 percent renewable energy. All that this movement needs is leadership from cities to lend their political, legislative, and financial weight. The world is ready.

“With a little creativity, cities are finding countless ways to overcome the many obstacles they may face in integrating renewable energy and energy efficiency.”

—Betsy Agar, Research Manager at Renewable Cities at Simon Fraser University Centre for Dialogue in Vancouver, Canada, and Michael Renner, Worldwatch Senior Researcher and Co-director of the State of the World report, in “Chapter 10: Is 100 Percent Renewable Energy in Cities Possible?”

What solutions exist to move urban energy systems toward sustainability?

Kats: The energy efficiency industry faces a crisis of opportunity. Energy efficiency is increasingly recognized as indispensable if we hope to avoid the most-severe climate change costs. But energy efficiency is underfunded and is treated as a second-class energy choice.

To meet emissions reduction targets, new buildings must become far more energy-efficient, with a rapidly growing portion of new buildings achieving zero or near-zero net emissions—primarily through energy efficiency. Even more importantly, retrofits need to go from being relatively shallow today to being deep—achieving 40-plus percent reductions in building energy use rather than the 10–20 percent reductions that are the norm today. How we finance and motivate energy efficiency must change rapidly for energy efficiency to deliver on its promise of anchoring the global transition to a low-carbon economy.

“Energy efficiency is the most cost-effective and largest path to CO2 reduction in existing buildings.”

—Gregory H. Kats, President of Capital E and Managing Director of ARENA Investments LLC, in “Chapter 9: Energy Efficiency in Buildings: A Crisis of Opportunity”

Cumbers: The term “remunicipalization” has become associated with a global trend to reverse the privatization wave that swept many countries—both industrialized and developing—in the 1980s and 1990s. Global privatization initiatives have not delivered the cost efficiencies, performance improvements, and infrastructure investment and modernization that their advocates had promised.

The remunicipalization trend is associated primarily with the water sector; however, the push to take back formerly privatized resources and services into local forms of public ownership and control is happening in the transport, waste management, energy, housing, and cleaning sectors as well. Reclaiming public services could lead to the development of integrated local strategies to tackle climate change, encourage energy efficiency, and advance renewable energy solutions.

“It is important to develop new and decentralized forms of public ownership that engage citizens and social movements in the battle against climate change.”

—Andrew Cumbers, professor of regional political economy at the University of Glasgow, in “Chapter 16: Remunicipalization, the Low-Carbon Transition, and Energy Democracy”

The responses above are excerpted from chapters by contributing authors in Can a City Be Sustainable?, a State of the World report. Want to hear from these and other urban experts? Join us on May 10, 2016 for the launch symposium in Washington, D.C. or livestream online.

Cities are the world’s future. Today, more than half of the global population—3.7 billion people—are urban dwellers, and that number is expected to double by 2050. There is no question that cities are growing; the only debate is over how they will grow. Will we invest in the physical and social infrastructure necessary for livable, equitable, and sustainable cities? In the latest edition of State of the World, the flagship publication of the Worldwatch Institute, experts from around the globe examine the core principles of sustainable urbanism and profile cities that are putting them into practice. Check out an excerpt of the book below.