Unnatural Selection

How We Are Changing Life, Gene by Gene

200 pages

6 x 9

Download the PDF here.

Gonorrhea. Bed bugs. Weeds. Salamanders. People. All are evolving, some surprisingly rapidly, in response to our chemical age. In Unnatural Selection, Emily Monosson shows how our drugs, pesticides, and pollution are exerting intense selection pressure on all manner of species. And we humans might not like the result.

Monosson reveals that the very code of life is more fluid than once imagined. When our powerful chemicals put the pressure on to evolve or die, beneficial traits can sweep rapidly through a population. Species with explosive population growth—the bugs, bacteria, and weeds—tend to thrive, while bigger, slower-to-reproduce creatures, like ourselves, are more likely to succumb.

Monosson explores contemporary evolution in all its guises. She examines the species that we are actively trying to beat back, from agricultural pests to life-threatening bacteria, and those that are collateral damage—creatures struggling to adapt to a polluted world. Monosson also presents cutting-edge science on gene expression, showing how environmental stressors are leaving their mark on plants, animals, and possibly humans for generations to come.

Unnatural Selection is eye-opening and more than a little disquieting. But it also suggests how we might lessen our impact: manage pests without creating super bugs; protect individuals from disease without inviting epidemics; and benefit from technology without threatening the health of our children.

"[An] examination of rapid evolution driven by artificial poisons. [Monosson's] tour takes in antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria, herbicide-resistant agricultural weeds, DDT-resistant bedbugs and the blue crabs of Piles Creek, New Jersey. Living in a soup of pollutants including mercury and hydrocarbons, these decapodal survivors display altered behaviours as well as resistance. Monosson ends with a thought-provoking look at epigenetics—evolution "beyond selection"."

Nature

"This fascinating and thought-provoking book...Monosson eloquently and in layman’s terms describes how life is resilient and details case studies of organisms that have rapidly evolved to overcome whatever (usually chemical) ways of killing them we humans have concocted."

National Nurse

"...a stealth lesson in basic biology — just the book to give to a friend or family member who thinks that evolution has little to do with day-to-day practicalities."

Los Angeles Review of Books

"disturbing but fascinating...bright, clear, and accessible prose...A concise book with a powerful message."

Booklist

"WOW! This deceptively slender book packs a helluva powerful punch....Unnatural Selection is an engaging and eye-opening book that is essential reading for everyone—city dwellers and country folk alike—who lives on planet Earth....Like reading a dystopian novel, this book will capture your imagination and keep you awake into the wee hours. But unlike a dystopian novel, the author actually proposes evolutionarily-sound strategies for what we can do to stop the damage before it becomes lasting."

The Guardian's GrrlScientist blog

"It is an honest attempt to wake us up and realize the bigger and more complex picture nature shows us."

San Francisco Book Review

"Unnatural Selection is a well-written book in the tradition of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. It usefully updates that epochal work, engagingly presenting new research on the impact of chemical products from herbicides to antibiotics, both on other species and on ourselves. Despite its elegant brevity, it covers a satisfying breadth of ecological and evolutionary concerns in environmental toxicology. It can be safely offered as recommended reading for biology undergraduates, congressional staffers, or general readers who are concerned about the environment."

Trends in Ecology & Evolution

"Toxicologist Monosson looks at the alarming effects of rapid evolution caused by pesticides, antibiotics and pollutants."

Toronto Star

"The power of evolution, toxicologist Monosson (Evolution in a Toxic World) demonstrates, is quite amazing: when strong selective pressure is coupled with short generation times, significant changes in populations can occur over very brief intervals. ... She concludes with an interesting, if tangential, discussion of epigenetics."

Publishers Weekly

"Part science-lover’s paradise, part horror novel, Monosson describes these human-influenced evolutionary terrors in fascinating detail."

Daily of the University of Washington

"Unnatural Selection is eye-opening and more than a little disquieting."

Science Book A Day

"Emily Monosson, an environmental toxicologist, describes in compelling and occasionally frightening detail how humans are the driving force behind the rapid evolution among cancer cells, bacteria, weeds, bedbugs and other creatures."

The Nature Conservancy's Science Chronicles

"If you’ve ever wondered why you should care about evolution, Unnatural Selection is the book for you. And if you haven’t wondered that, you need to read this to find out what you’re missing. Environmental toxicologist Emily Monosson, with prose that is clear, succinct, and so interesting it’s hard to put the book down, explains how people are speeding up an evolutionary arms race both within and around us. And that arms race is between us, disease, pests, and many other species on Earth. A thoroughly engaging read for anyone that cares about the role of humans on our planet."

Anthony Barnosky, Professor, Department of Integrative Biology, UC Berkeley and author of Heatstroke

"[A] remarkable book...this book should be read by anyone who cares about the environment in the Anthropocene."

Environment, Development, and Sustainability

"Darwin's evolutionary laboratories were far flung islands and exotic shores. Emily Monosson uncovers rapid evolution much closer to home, in our farm fields, cities and even among the microbes in our own bodies. Through personal stories and scientific discovery, this readable, accessible account explores the evolution that Darwin never knew."

Stephen R. Palumbi, Professor of Marine Science, Stanford University and author of The Evolution Explosion

"In a world where the denial of evolution – or its importance – is still common, this book should convert even the most entrenched skeptics."

Andrew Hendry, Professor, Redpath Museum & Department of Biology, McGill University

"Prepare for the unexpected! Evolution has consequences and when we rapidly drive the process, through our profligate use of antibiotics and toxic chemicals, we should be prepared for unexpected outcomes. Monosson succinctly shows us how and why our inability to control diseases and pests and grow sufficient food to eat is an inevitable product of our anthropogenic toxification of the Earth. Eye opening and timely."

Daniel T. Blumstein, Professor & Chair of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, UCLA

Introduction: Life Changing Chemicals

PART I. Unnatural Selection in a Natural World

Chapter 1. Discovery: Antibiotics and the Rise of the Superbug

Chapter 2. Prevention: Searching for a Universal Vaccine

Chapter 3. Treatment: Beyond Chemotherapy

Chapter 4. Defiance: Rounding Up Resistance

Chapter 5. Resurgence: Bedbugs Bite Back

PART II. Natural Selection in an Unnatural World

Chapter 6. Release: Toxics in the Wild

Chapter 7. Evolution: It’s Humanly Possible

PART III. Beyond Selection

Chapter 8. Epigenetics: Epilogue or Prologue?

We live in an age of pesticide and antibiotic overuse. One outcome is resistance, increasing pesticide use and contamination and fears that we are entering the “post-antibiotic era”. We are addicted to all sorts of commercial chemicals.

So what’s next? How do we break the cycle? While industry may see opportunities for newer and more powerful chemicals, there’s another way out.

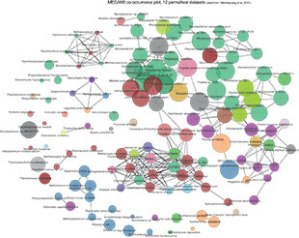

We need to rethink our strategy. One of the most promising and exciting (the newest-oldest solution) is allying with Nature. The metagenomics boom is bringing to light microbes by the billions. More of them good than “bad.” For over a century, we have narrowed our focus on the pathogens. One disease after another: C. diff, MRSA, Borrelia in our bodies and Late blights, early blights, wilts and rots in our fields. But now agricultural and medical scientists for the first time ever are becoming acquainted with Earth’s microbiome in a big way. The invisible world whose only citizens we’ve come to know were those we could capture and culture. A mere fraction. Now we are getting to know the whole neighborhood. The communities where pathogens mix and mingle with others, where those most likely to run amok are managed by the neighbors. Many produce their own chemicals: small molecules for communication and for protection — antibiotics produced on a microbial scale keeping microbial communities in check. Others simply out-compete otherwise aggressive undesirables.

We need to rethink our strategy. One of the most promising and exciting (the newest-oldest solution) is allying with Nature. The metagenomics boom is bringing to light microbes by the billions. More of them good than “bad.” For over a century, we have narrowed our focus on the pathogens. One disease after another: C. diff, MRSA, Borrelia in our bodies and Late blights, early blights, wilts and rots in our fields. But now agricultural and medical scientists for the first time ever are becoming acquainted with Earth’s microbiome in a big way. The invisible world whose only citizens we’ve come to know were those we could capture and culture. A mere fraction. Now we are getting to know the whole neighborhood. The communities where pathogens mix and mingle with others, where those most likely to run amok are managed by the neighbors. Many produce their own chemicals: small molecules for communication and for protection — antibiotics produced on a microbial scale keeping microbial communities in check. Others simply out-compete otherwise aggressive undesirables.

The rise of C. diff in humans following antibiotic treatment in vulnerable patients and the efficacy of fecal transplants — essentially replacing a gut community bereft of a healthy neighborhood, with a more properly functioning community is one example. While on the farm agriculturists are buzzing about the potential for microbes to wean large conventional growers off of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides (or at least turn the latter into supplementals rather than necessities) is providing a host of other examples from biopesticides to probiotics for the farm. For more about this see The Littlest Farmhands recently published in Science.

We are chemical addicts. Returning to Nature is like going back to the future, with an opportunity to change the timeline. Adjust our course. In the near future perhaps we can rely less on our synthetic chemistry and more on Nature’s capacity to manage her own.

Evolution: More frightening than you might think. Photo by Lenore Edman, used under Creative Commons licensing.

If you're looking for something scary this Halloween, look no further. Today's excerpt comes from Unnatural Selection: How We Are Changing Life, Gene by Gene, which, completely coincidentally, we published earlier this week. The book explores the biological fright fest we've unleashed with the plethora of chemicals on which the modern lifestyle relies. Monosson studies a spooky cast of characters, from shifty flu viruses and Grim Reaper-esque cancer cells to fish that thrive in Superfund sites. In the excerpt below, we've shared the creepy-crawliest chapter, which looks at why bedbugs have returned to plague us despite the chemicals we've flung at them.

Happy reading, and happy Halloween!

With the end of COP 21 and the signing of the historic Paris Agreement, it’s not just countries that are thinking about how to reduce emissions—individuals are reflecting on how their habits and actions impact climate change as well.

Island Press authors shared what they’re doing to reduce their carbon footprints and, in some cases, what more they could be doing. Check out their answers and share your own carbon cutbacks—or vices—in the comments.

Jason Mark, author of Satellites in the High Country:

Very much like the Paris Climate Accord itself, ecological sustainability is a process, not a destination. Which, I'll admit, is a squirrely way of saying that I'm doing my best to reduce my carbon footprint. I ride my bike. I take mass transit. Most days my car never leaves the spot in front of our home. Most importantly, I have sworn off beef because of cattle production's disproportionate climate impact. The (grass-fed, humane) burger still has a siren song, but I ignore it.

Grady Gammage, author of The Future of the Suburban City:

I drive a hybrid, ride light rail to the airport and don’t bother to turn on the heat in my house (which is possible in Phoenix). My greatest carbon sin is my wood burning fireplace. I don’t use it when there’s a “no burn” day, but otherwise, I have a kind of primordial attraction to building a fire.

John Cleveland, co-author of Connecting to Change the World:

We just installed a 12 KW solar array on our home in New Hampshire. At the same time, we electrified our heating system with Mitsubishi heat pumps. So our home is now net positive from both an electricity and heating point of view. We made the solar array large enough to also power an electric car, but are waiting for the new models that will have more range before we install the electric car charger. The array and heat pumps have great economics. The payback period is 8-years and after that we get free heat and electricity for the remainder of the system life — probably another 20+ years. Great idea for retirement budgets!

Dan Fagin, author of Toms River:

Besides voting for climate-conscious candidates, the most important thing we can do as individuals is fly less, so I try to take the train where possible. I wish it were a better option.

Photo by Bernal Saborio, used under Creative Commons licensing.

Darrin Nordahl, author of Public Produce:

The United States is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China, and how we produce food in this country is responsible for much of those emissions. From agriculture, to the fossil fuels needed to produce bags and boxes for pre-packaged food, to the burning of gas and oil to transport both fresh produce and pre-packaged food, I have discovered I can reduce my carbon footprint with a simple change in my diet. For one, I avoid processed food of any sort. I also grow a good portion of my vegetables and herbs and, thankfully, local parks with publicly accessible fruit trees provide a modicum of fresh fruit for my family. We also eat less meat than we used to and our bodies (and our planet) are healthier because of it.

Yoram Bauman, author of The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change:

I try to put on warm slippers or other extra layers around the house in order to not have to heat the house so much, but I still like to take long hot showers. (Maybe those two things are connected).

Rob McDonald, author of Conservation for Cities:

I try to pay attention to my daily habits that make up a lot of my carbon footprint. So I bike to work, or take mass transit. That gets rid of the carbon footprint of driving. I also try to only moderately heat or cool my home, so I’m not burning a lot of energy doing that. The biggest component of my carbon footprint that I haven’t managed to cut is for travel. I have to travel once or twice a month for my job, and unless it is a trip in the Northeast (when I can just use Amtrak!), I am stuck travelling. The carbon footprint of all that air travel is huge. I try to do virtual meetings, rather than travel whenever I can, but there still seems to be a big premium people place on meeting folks face to face.

Emily Monosson, author of Unnatural Selection:

We keep our heat really low in the winter (ask our teenage daughter, it's way too cold for her here!) and I hang my clothes on the line in the summer. Because it’s so cold, I love taking really hot long showers. I should also hang my clothes in the winter too, and ditch the dryer.

Jonathan Barnett and Larry Beasley, co-authors of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs:

We both live in a town-house in the central part of a city – on opposite sides of the continent: one in Philadelphia the other in Vancouver. Our neighborhoods have 100% walk scores. We each own one car, but don’t need to drive it very much - most of the time we can go where they need to on foot. We wrote our book using email and Dropbox. What they still need to work on is using less air travel in the future.

Jan Gehl, author of Cities for People:

I live in Denmark where 33% of the energy is delivered by windmills. A gradual increase will happen in the coming years. As in most other countries in the developed world, too much meat is on the daily diet. That is absolutely not favorable for the carbon footprint. It sounds like more salad is called for in the future!

Photo by Katja Wagner, used under Creative Commons licensing.

Suzanne Shaw, co-author of Cooler Smarter:

Cooler Smarter: Practical Steps for Low Carbon Living provides a roadmap for consumers to cut their carbon footprint 20 percent (or more). My approach to lowering my carbon footprint has gone hand in hand with saving money through sensible upgrades. Soon after I purchase my 125-year-old house I added insulation, weather stripping and a programmable thermostat. When I needed a new furnace, I swapped a dirty oil furnace to a cleaner, high-efficiency natural gas model. And now have LED bulbs in every fixture in the house, Energy Star appliances throughout, and power strips at my entertainment and computer areas. This summer, I finally installed solar panels through a 25-year lease (zero out-of-pocket expense). In the month of September, I had zero emissions from electricity use. Living in the city, I am fortunate to have access to public transportation and biking, which keeps our household driving to a minimum.

Peter Fox-Penner, author of Smart Power Anniversary Edition:

I’m reducing my footprint by trying to eat vegan, taking Metro rather than taxis or Ubers, and avoiding excess packaging. Right now I travel too much, especially by air. P.S. Later this year I’ll publish my carbon footprint on the website of the new Boston University Institute for Sustainable Energy. Watch for it!

Carlton Reid, author of Roads Were Not Built for Cars:

Our family has a (small) car but I cycle pretty much all of the time. My kids cycle to school (some days) and my wife cycles to work (sometimes). It’s useful to have the car for some journeys, long ones mostly, but having a family fleet of bikes means we don’t need a second car. Reducing one’s carbon footprint can be doing less of something not necessarily giving up something completely. If everybody reduced their car mileage (and increased their active travel mileage) that would be good for the planet and personally: win/win.

With more and more cases of Zika virus being reported, some experts are calling for the use of DDT to combat the mosquitoes that transmit it. We asked Emily Monosson, author of Unnatural Selection and Evolution in a Toxic World to weigh in on the proposed use of pesticides, and what else we can do to protect ourselves from disease-carrying insects.

Over the past fifteen years I’ve experienced the spread of Lyme disease in my own backyard. Within a matter of years, the field where my daughter used to unpack her little wicker basket—laying out a blue-checked table cloth and two teacups painted with images of Winnie-the-Poo and Eeyore—has transformed from a field of emerald green grass and wildflowers to a danger-zone where the consequence of a Sunday afternoon tea-party may be a bout with Lyme.

In little over a decade, the Lyme bacterium, the deer ticks, the white-footed mouse, and deer that host the ticks have all become more prevalent. This is our new reality. Human-induced change from altered habitats, reductions in predators, and a warming climate are enabling pest and pathogen to move into new spaces. And Lyme is a harbinger of things to come.

Mosquitoes, along with their disease-causing hitchhikers like West Nile, Equine encephalitis, Dengue, and now Zika, are on the move, finding new habitats and naïve populations ripe for infection. Just as Lyme has made tick experts out of us all (no, that one is just a dog tick), we are on a first-name basis with mosquitoes like Aedes and Culex. Here in the Northeast dozens of mosquito varieties bite, buzz, and mate. Some inject pathogens, most don’t. Each has their own preferences and habits. Culex pipiens carries West Nile and favors biting birds to humans; Coquillettidia perturbans is a midsummer’s carrier of Eastern Equine Encephalitis and feeds upon anyone and everyone from birds to humans; Ochlerotatus sticticus is another daytime disease carrying biter. Others prefer non-human mammals, or frogs, or even snakes. In Massachusetts alone there are over fifty varieties of mosquitoes. Of all disease-carrying insects, mosquitoes are the hands-down winners as the world’s greatest menace. But, of the thousands of known varieties worldwide, only a few hundred bite humans, and fewer transmit disease. Then again, it only takes one.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is a relative newcomer to the Northeast. First identified nearly 30 years ago in a Texas dump, the aggressive blood-sucker, likely aided by a warming climate, has marched northward over the decades. Known to transmit as many as twenty different kinds of pathogens in different regions around the globe, health experts fear that someday soon the tigers will be delivering pathogens like Dengue, chikungunya, or Zika to more northern regions of the U.S.

The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus is known to transmit as many as twenty different kinds of pathogens in different regions around the globe, including the United States. By James Gathany/CDC, via Wikimedia Commons

Zika and Dengue are also transmitted by Aedes aegypti. Warmer-weather mosquitos which, like the tiger, are particularly well adapted for life amongst humans with a penchant for laying their eggs in roadside bottle-caps, abandoned tires, or backyard tarps. A habit that makes them particularly successful breeders—free from natural predators like fish or dragonfly larvae—and difficult to eradicate with pesticide spray programs. Centuries ago, yellow fever outbreaks in Northeast cities from Boston to Philadelphia suggest that Aedes, likely carried aboard ship from far-flung ports, survived long enough to spread disease before succumbing to cool weather. While these beasts of the subtropical wilds haven’t yet made a go of it in the north, climate change may alter that.

Those of us who remember mosquito-free evenings of the 60s and 70s probably also remember the fog of DDT trucks. With the advent of synthetic chemistry, we turned to miraculous chemical cures like DDT and other powerful pesticides. It seemed there wasn’t a pest we couldn’t conquer. A few decades later our hubris was rewarded with a catastrophic decline in raptors and resistance in targeted insects. Plenty of communities still spray next-generation pesticides (like resmethrin and biologically-based bacterial sprays) but for every chemical cure there is, or will likely soon be, a resistant population. Pests with amped up detoxification systems or target sites with reduced sensitivity. Not to mention harm done to the innocent bystanders, beneficial insects that prey upon pests or pollinate plants. And, for a species like Aedes, pesticide from a large-scale spray program may not find its way into that bottle cap, or dog bowl or old tire. For these buggers, control requires a more personal touch: a weekly scan of the yard, junk yard, or parking lot. With a flight range of a couple hundred meters, clearing a yard or a neighborhood block of mosquito breeders can go a long way towards control.

So far, mosquitos carrying Zika haven’t yet been reported in the continental U.S.; though it is likely only a matter of time. And if it’s not Zika, some other mosquito-borne virus will be coming to our neighborhoods someday soon.

There is some hope. Most notably, scientists have engineered mosquitoes to produce offspring destined to die before they are old enough to reproduce. This strategy is already in trials in Brazil, Florida, and elsewhere. Because reproduction is the Achilles heel of the evolutionary process (inheritance, inheritance, inheritance!), it is a strategy unlikely to be circumvented by evolved populations. And while we have learned time and again that it is difficult to fool Mother Nature, we also need to consider the consequences of actually doing so. Like, the consequences of world without Aedes or other mosquitoes. Most ecologists aren’t too concerned. Predators that feed on mosquitoes or larvae will find other food; other pollinators will fill in where mosquitoes left off. But the end of mosquitoes isn’t in our near future; at best the strategy may work on localized populations or regionally rather than going global.

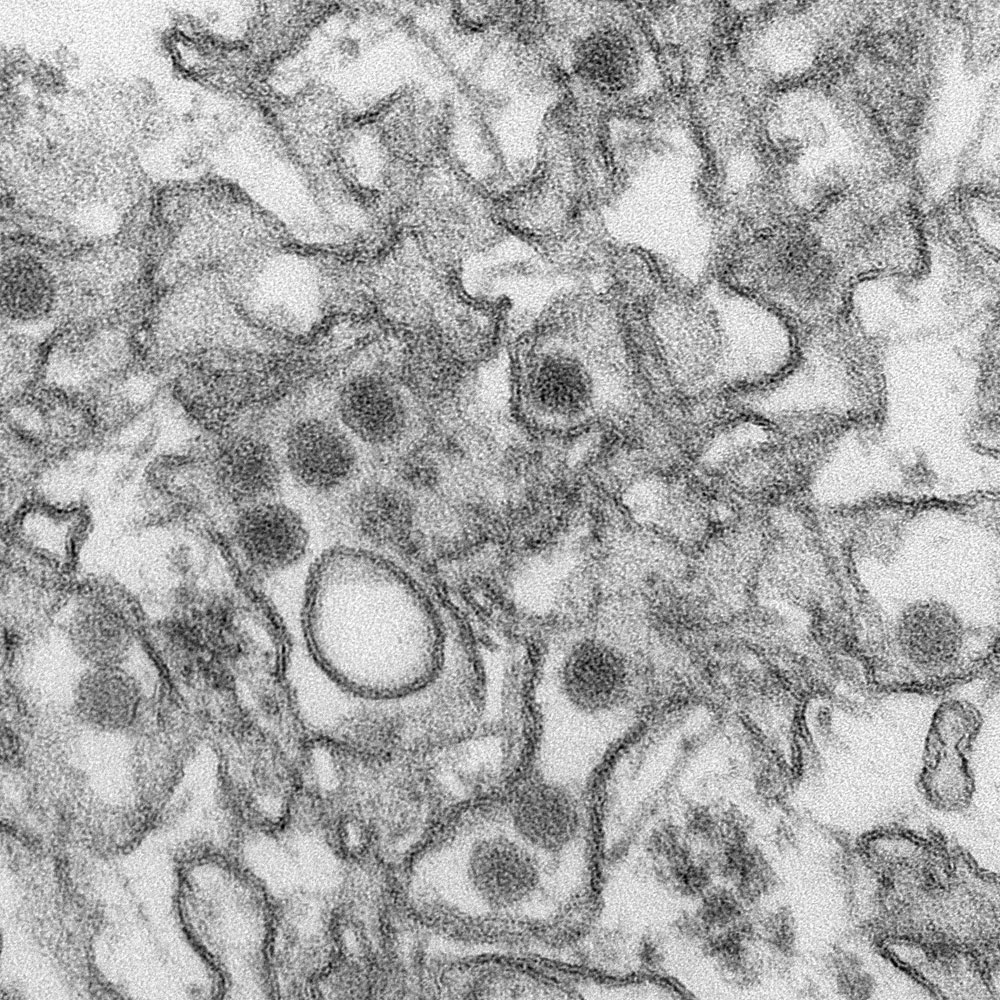

Transmission electron micrograph of Zika virus. By CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith, via Wikimedia Commons

On the flip side, if we can’t stop the pest, perhaps we can stop the pathogen. Mosquito-borne diseases have killed hundreds of millions of people (approximately one million individuals each year). Vaccines have saved many more. There aren’t yet vaccines for West Nile and chikungunya (though a vaccine for Dengue, twenty years in development, just became available in some countries), and of course Zika is prompting vaccine developers to scramble, promising accelerated vaccine development and production. Even so, it may be years before vaccines enable us to shed our long sleeves and ditch the mosquito repellent.

So what are our options? After nearly a century of resting on our chemical laurels, we need to think differently. There is no quick fix. As with Lyme we will all need to become a little more wary, a lot less cavalier and a bit more humbled by Nature. We will need to be more strategic about how and when we use pesticides, how we dress when we go outside, and perhaps even when we go outside. We also need to be more aware of our contribution to the problem. But that doesn’t mean we need to cloister ourselves indoors.

When we venture out into the field during tick season (a depressingly longer stretch of time each year), we expect ticks. Years ago we joked about “tick-checks.” Now they are a part of the daily routine. We scoffed at “birding couture:” the long sleeves, light clothing, pants tucked into socks. Not so now. Maybe it’s time to dig out that bug head net I bought for gardening but never wore. Not so comfortable, but what the heck. And sweeping around the yard every few days drying out the mosquito breeders will definitely become part of the spring and summer routine. As much as I know not to leave standing water, the dog bowl has nurtured plenty of newly hatched mosquitos over the years. With our ever-changing world, we don’t have to live in fear, but we do need to live more aware.

Gonorrhea. Bed bugs. Weeds. Salamanders. People. All are evolving, some surprisingly rapidly, in response to our chemical age. In Unnatural Selection, newly available in paperback, Emily Monosson shows how our drugs, pesticides, and pollution are exerting intense selection pressure on all manner of species. And we humans might not like the result. Monosson reveals that the very code of life is more fluid than once imagined. When our powerful chemicals put the pressure on to evolve or die, beneficial traits can sweep rapidly through a population. Species with explosive population growth—the bugs, bacteria, and weeds—tend to thrive, while bigger, slower-to-reproduce creatures, like ourselves, are more likely to succumb.

Unnatural Selection is eye-opening and more than a little disquieting. But it also suggests how we might lessen our impact: manage pests without creating super bugs; protect individuals from disease without inviting epidemics; and benefit from technology without threatening the health of our children. Check out an excerpt below.

Download the pdf here.

This post was originally published on Emily Monosson's blog and is reposted with permission.

In light of the fuss over Robert Di Niro and the movie Vaxxed; if anyone needs reminding of the value of vaccines, take a look at this diagram of 20th Century Death. These are estimates as they say but even so the numbers are humbling. I won’t go into the story behind the movie and its writer, director and one-time (now unlicensed) doc, that has been covered plenty (instead here is an interesting NYT article about the developer of the measles vaccine, Dr. Maurice Hilleman.)

Though measles occupies one of the smaller circles, it is credited with killing approximately 97 million worldwide. The Disneyland outbreak also reminds us of days gone by (at least here in the U.S.) when viruses from measles to smallpox spread like wildfire. It is easy to forget when we don’t have to care.

Viruses don’t just kill. And while many of us weather the storm just fine, viruses that cross the placenta can also cause birth defects and death. That is something else we’ve forgotten, although with Zika, Nature is reminding of our place in the world of pathogens. Zika has recently been linked to microcephaly, birth defects and other neurological problems.

Years ago there was Rubella, a virus notorious for causing miscarriage, postnatal death, organ damage and intellectual disability. I am sure my daughter has never heard of it and likely won’t worry about it should she ever become pregnant. She was protected from an early age with the MMR (mumps, measles and rubella) vaccine. Unlike diseases spread from one human to another, there are other ways to try to control the spread of Zika, but mosquito control is a whole other kind of challenge (and, Zika can be spread sexually – the CDC has just issued a warning). If I were of childbearing age, and lived in a high-risk region I would be hoping for a Zika vaccine soon.

Vaccines aren’t perfect. But the number of lives saved and birth defects prevented is undeniable.

This post originally appeared on Emily Monosson's blog Evolution in a Toxic World and is reposted here with her permission.

We were closing in on the end of a glorious spring weekend when my husband discovered the bag. “Any chance you left this lying around — empty?” he’d asked holding the remnants of a one pound bag of Trader Joe’s raisins I’d purchased just the day before with images of molasses filled hermit cookies in mind. I hadn’t, nor had I made the hermits, or chewed away the corners of the bag. Apparently Ella (pictured below) had consumed every last raisin, save the two handfuls my husband snacked on before leaving the bag on the living room floor.

“I bet she won’t be feeling too good later,” he’d said, eyeing the ever expectant dog sitting at our feet, tail wagging, hoping for a few more of the sweet treats. He had no idea. Nor had I. Not really. I’d had some inkling of a rumor that raisins and grapes were bad for dogs, but never paid too much attention. It’s one of those things you hear at the same time you hear of people treating their dogs to grapes. So, to be safe (and feeling a bit sheepish that, as a toxicologist I ought to have an answer to the raisin question) I suggested he call the vet. And that is when we fell into the raisin hell rabbit hole. Five minutes later dog and husband were on their way to the doggie ER, pushed ahead of the mixed breeds and the Golden and the sad-sack blood hound and their people waiting for service.

Meanwhile I took to Google. Was this really a life or death dog emergency? If so, why weren’t we more aware? I get it, that one species’ treat can be another’s poison. Differences in uptake, metabolism, excretion. Feeding Tylenol to cats is a very bad idea (as if you could feed a cat a Tylenol tablet). And pyrethrin-based pesticides in canine flea and tick preventions are verboten in felines. The inability to fully metabolize and detoxify these chemicals can kill a particularly curious cat. But raisins in dogs? Not so clear. Googling will either send you racing off to the vet or to bed. You may even toss your best friend a few grapes for a late night treat, smug in the knowledge that those who have bought into the hysteria are hemorrhaging dollars while paying off the vet school debt of a veterinarian who is gleefully inducing their dog to vomit, while you snooze.

Even Snopes the online mythbuster was confused (though they suggest erring on the side of caution.)

By the time I arrived at the clinic, uncertain enough to follow up on husband and dog, Ella’s raisin packed gut under the influence of an apomorphine injection (a morphine derivative which induces vomiting in seconds) had done its thing. While Ben and I waited for Ella’s return in the treatment room, somewhat relieved, we played, “Guess how much?” Treatment with a drug, time with the vet, multiplied by the “after hours factor” this being a Sunday evening after all, we’d settled on something in the $300-400 range.

“Ella did great,” said the vet tech who’d taken her from Ben and hour or so earlier. “A pile of raisins came up. Some were even still wrinkled!” Phew. Potential disaster averted. We’d accepted that it’d likely cost a few hundred – but we’d soon be heading home with Ella in the back seat. We had a good laugh about the revisit of the raisins. But the vet tech wasn’t finished. That was just the first step. “So now we’ll give her some activated charcoal,” she continued “and you can pick her up on Tuesday.” Total estimated low-end estimate? A bit over $1000. Paid up front (I have wondered what would have happened if we couldn’t pay – but that is a whole other issue). Apparently we had underestimated the price of a good vomit.

Continue reading the full post on Evolution in a Toxic World.

This post originally appeared on Emily Monosson's blog and is reposted with permission here.

“Dear List, does anyone have access to this article?” A simple request posted to a list serve of scientists and policy makers. Someone suggested she try Sci-Hub; another sheepishly suggested #icanhazpdf.com; until someone else pointed out the illegality of those sites. One essentially suggested the author find her own damn article, even if it means paying for it. Eventually the list settled into a discussion about access; and about the scientific haves and the have-nots. Literature is our lifeblood. Quotes and citations and names and dates fill the chapters of dissertations, the paragraphs of research papers and review articles and reports. Who did what first; how many others confirmed; where did it go wrong; the controversies; the methods; the findings; interpretations and conclusions. What is lacking? And maybe most importantly, where next?

Access to scientific literature looms large, particularly for those of us working on the edge or outside of academia and even for many of those within. I am particularly sensitive to the situation, in part because I work in fear of losing the access I’ve enjoyed for the past twenty years. Which is part of the problem. Too many of us haves, have no idea how stifling lack of access is for the have nots. For much of my career I have worked obstinately, proudly and maybe sometimes too stubbornly outside of mainstream institutions – but I have enjoyed a non-teaching adjunct position with my local university for which I have been extremely grateful. I could not have done this for so long without access.

I am not alone. After the list-serve hullabaloo – I surveyed the list and elsewhere seeking experiences other than my own. Many like the Ronin Scholars are independent scientists; doing the work they love, outside of the Institution. Some are retired, or recent grads, or mid-career scientists. Basically all over the career map. Many do not have the access they need.

Access, wrote one respondent is “vital.” Without it writes another, “I would be lost”. “It is fundamental.” “100% essential.” You get the picture. But this we all know. Access to science, is what enables science. If we, as a scientific community, care about strengthening our community – particularly outside of academia — if we care about retaining scientists, then we must all care about access.

“One of the four canonical ‘norms of science’ identified by sociologist Robert K Merton in the mid-20th c. was communism or communalism – open sharing of methods and results,” writes Brent Ranalli, a friend, colleague and student of science history. I had asked him about the role of knowledge sharing in science.

“Merton’s reputation has waxed and waned, but he did put his finger on something. If you look back to the 1600s, one of the big changes that marked the scientific revolution was a greater open-handedness. Whereas alchemists viewed their knowledge as esoteric or as a trade secret, chemists tried to be as transparent as possible. Scientists in different countries coached each other through reproducing experiments. The first scientific journals were written to spread news of experiments and observations as broadly as possible. For some participants, there was a millenarian religious aspect to this—doing God’s work by spurring scientific participation and collaboration and innovation that would lead to a Golden Age.”

Now, as we enter the Golden Age of information and technology – somewhere, somehow, this scientific information increasingly became locked away behind paywalls. Creating a system of scientific Haves and Have-nots, as university libraries become gateways open to those with the right netIDs. As increasing numbers of us wander from the academy, whether working for non-profits, as high-school teachers, writers or god-damn independents – we risk losing access to this trove of essential data. And the larger scientific community, I think, risks losing us along with all the time, and money and knowledge it took to train us.

Continue reading the full post here.

This blog originally appeared on Emily Monosson's blog and is reposted here with permission.

The New York Times article, Doubts About the Promised Bounty of Genetically Modified Crops rightly argues that herbicide resistant GMOs haven’t reduced the use of chemicals on the farm. But by equating genetic modification with herbicide resistant plants, this article is misleading. Many of us agree there are problems with herbicide resistant plants, and that misuse, overuse and eventually resistance in weeds has put users on a toxic herbicide treadmill.

But GMO technology isn’t just about herbicide resistance. It can also be deployed to reduce pesticide use and, there are new ways to engineer plants and animals that don’t mix and match genetic material from vastly different species. Take potatoes engineered to resist one of the most destructive potato pathogens, late blight, the disease that devastated Irish potato crops and kicked off the Great Famine. When blight strikes it can destroy crops so rapidly that growers often use multiple applications (sometimes more than a dozen a season) of toxic fungicides to prevent disease. A decade ago 2000 tons of fungicide were applied to potato crops just here in the states. In turn, blight has evolved to resist many of those pesticides. For such an aggressive disease, genetic engineering may be one of the few options for growers wishing to reduce their use of toxic chemicals. In this case rather than inserting genes from a totally foreign species, one approach is to insert disease resistance genes from a more resilient relative.

The potatoes recently engineered by scientists at The Wageningen University Research in the Netherlands for example are, they say, indistinguishable from the potatoes we love to bake and fry. Why use engineering when a grower might breed for resistance, an ages old practice? One reason is speed. Engineering enabled the production of a disease resistant crop in three yearsrather than three decades. And unlike transgenics like Roundup Ready and Bt crops which introduce foreign genes onto an unfamiliar “genetic landscape” of the target species – the GMO that everybody loves to hate – these so-called cisgenic potatoes introduce new traits into familiar territory, reducing concerns for unintended consequences. Additionally, Wageningen University Research retains the intellectual property and offers non-exclusive licenses to parties interested in working with the genes or resistant plants in an effort to thwart corporate control. The cisgenic process along with other techniques like gene editing are providing opportunities for genetic engineering that call for reevaluation. Genetic engineering is a technology, not a product.

Below: an image from the Hartsfield-Jackson airport. Couldn’t resist, check it out next time you’re there.

This holiday season, give the gift of an Island Press book. With a catalog of more than 1,000 books, we guarantee there's something for everyone on your shopping list. Check out our list of staff selections, and share your own ideas in the comments below.

For the OUTDOORSPERSON in your life:

Water is for Fighting Over...and Other Myths about Water in the West by John Fleck

Anyone who has ever rafted down the Colorado, spent a starlit night on its banks, or even drank from a faucet in the western US needs Water is for Fighting Over. Longtime journalist John Fleck will give the outdoors lover in your life a new appreciation for this amazing river and the people who work to conserve it. This book is a gift of hope for the New Year.

Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man by Jason Mark

Do you constantly find your friend waxing poetic about their camping tales and their intimate connection to the peaceful, yet mysterious powers of nature? Sounds like they will relate to Jason Mark’s tales of his expeditions across a multitude of American landscapes, as told in Satellites in the High Country. More than a collection of stories, this narrative demonstrates the power of nature’s wildness and explores what the concept of wild has come to mean in this Human Age.

What Should a Clever Moose Eat?: Natural History, Ecology, and the North Woods by John Pastor

Is the outdoorsperson in your life all dressed up in boots, parka, and backpack with nowhere to go? Looking for meaning in another titanium French press coffeemaker for the camp stove? What Should a Clever Moose Eat leaves the technogadgets behind and reminds us that all we really need to bring to the woods when we venture out is a curious mind and the ability to ask a good question about the natural world around us. Such as, why do leaves die? What do pine cones have to do with the shape of a bird’s beak? And, how are blowflies important to skunk cabbage? A few quality hours among its pages will equip your outdoor enthusiast to venture forth and view nature with new appreciation, whether in the North Woods with ecologist John Pastor or a natural ecosystem closer to home.

Also consider: River Notes by Wade Davis, Naturalist by E.O. Wilson

For the CLIMATE DENIER in your life:

Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change by Yoram Bauman

This holiday season, give your favorite climate-denier a passive aggressive “wink-wink, nudge-nudge” with The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change featuring self –described Stand-up Economist Yoram Bauman and award-winning illustrator Grady Klein. Give the gift of fun, entertaining basic understanding of what is, undeniably and not up for subjective debate, scientific fact!

Also consider: Heatstroke by Anthony Barnosky, Straight Up by Joseph Romm

For the HEALTH NUT in your life:

Unnatural Selection: How We Are Changing Life, Gene by Gene by Emily Monosson

Give the health nut in your life the gift of understanding with Unnatural Selection. Your friends and family will discover how chemicals are changing life on earth and how we can protect it. Plus, they’ll read fascinating stories about the search for a universal vaccine, the attack of relentless bedbugs, and a miracle cancer drug that saved a young father’s life.

Also consider: Toms River by Dan Fagin, Roads Were Not Built for Cars by Carlton Reid,

For the ADVOCATE in your life:

Prospects for Resilience: Insights from New York City's Jamaica Bay by Sanderson, et. al

Need an antidote to the doom and gloom? Stressed-out environmental advocates will appreciate Prospects for Resilience: Insights from New York City's Jamaica Bay. It’s a deep dive into one of the most important questions of our time: how can we create cities where people and nature thrive together? Prospects for Resilience showcases successful efforts to restore New York’s much abused Jamaica Bay, but its lessons apply to any communities seeking to become more resilient in a turbulent world.

Ecological Economics by Josh Farley and Herman Daly

Blow the mind of the advocate in your life with a copy of Ecological Economics by the godfather of ecological economics, Herman Daly, and Josh Farley. In plain, and sometimes humorous English, they’ll come to understand how our current economic system does not play by the same laws that govern nearly every other system known to humankind—that is, the laws of thermodynamics. Given recent financial and political events, there’s a message of hope within the book as it lays out specific policy and social change frameworks.

Also consider: Tactical Urbanism by Mike Lydon, Cooler Smarter by The Union of Concerned Scientists

For the CRAZY CAT PERSON in your life:

An Indomitable Beast: The Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar by Alan Rabinowitz

The cat lovers in your life will lose themselves in An Indomitable Beast, an illuminating story about the journey of the jaguar. This is the perfect book for any of your feline loving friends, whether they want to pursue adventure with the big cats of the wild, or stay home with a book and cup of tea.

Also consider: The Carnivore Way by Cristina Eisenberg, Jaguar by Alan Rabinowitz

For the GARDENER in your life:

Wild by Design: Strategies for Creating Life-Enhancing Landscapes by Margie Ruddick

Give your favorite gardener an antidote to the winter blues. The lush photographs of Wild by Design, and inspirational advice on cultivating landscapes in tune with nature, transport readers to spectacular parks, gardens, and far-flung forests. This book is guaranteed to be well-thumbed and underlined by the time spring planting season arrives!

Also consider: Brilliant Green by Stefano Mancuso, Principles of Ecological Landscape Design, Travis Beck

For the STUBBORN RELATIVE in your life:

Common Ground on Hostile Turf: Stories from an Environmental Mediator by Lucy Moore

For the person keeping the peace in your family this holiday season, the perfect gift is Common Ground on Hostile Turf, an inspiring how to guide demonstrating it is possible to bring vastly different views together. This book gives lessons learned on setting down at the table with the most diverse set of players and the journey they take to find common grounds and results. If your holiday dinner needs some mediation, look to the advice of author Lucy Moore.

Also consider: Communication Skills for Conservation Professionals by Susan Jacobson, Communicating Nature by Julia Corbett

For the HISTORY BUFF in your life:

The Past and Future City: How Historic Preservation is Reviving America's Communities by Stephanie Meeks with Kevin C. Murphy

When it comes to the the future of our cities, the secret to urban revival lies in our past. Tickle the fancy of your favorite history buff by sharing The Past and Future City, which takes readers on a journey through our country's historic spaces to explain why preservation is important for all communities. With passion and expert insight, this book shows how historic spaces explain our past and serve as the foundation of our future.

Also consider: The Forgotten Founders by Stewart Udall, Aldo Leopold's Odyssey, Tenth Anniversary Edition by Julianne Lutz Warren

For the BUSINESS PERSON in your life:

Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature by Mark Tercek

For the aspiring CEO in your life who drools at phrases like "rates of return" and "investment," share the gift of Nature's Fortune, an essential guide to the world's economic (and environmental) well-being.

Also consider: Corporation 2020 by Pavan Sukhdev, Resilient by Design by Joseph Fiksel

This blog originally appeared on Emily Monosson's blog and is reposted here with permission.

Yesterday I read of a meningitis B outbreak at Oregon State University. Today, it’s the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, MA. MenB is a potentially lethal and easily spread infection particularly in settings where young adults gather together. As the university races to vaccinate tens of thousands of students, my thoughts turn to our daughter, a senior in college. A few years ago after writing a book chapter that included the history of meningitis B and the recent development of a vaccine, I had asked my daughter’s pediatrician (ironically in Amherst, MA) if she could receive the vaccination as she headed off for her sophomore year. They would not, stating that it was available only for those who had other health indications. Perhaps if it were more easily available, colleges would not have to react, and students would already be protected.

Below is an excerpt from that chapter about meningitis and the vaccine:

My father had just returned from the Navy, an apple-cheeked mischievous twenty year-old looking forward to his junior year in college when meningitis struck. It was 1946 and the last thing he recalled was brushing his teeth at home in the bathroom. For the next ten days he lay unconscious in a hospital bed his body fighting off an invisible army of bacterial invaders. Aided by the new miracle drug, penicillin, he survived, but not entirely unscathed. Shortly after recovery my father was jolted by brain seizures – his brain permanently damaged by the infection. For the remainder of his life he managed the condition with a combination of powerful antiepileptic drugs (while baffling his doctors by referring to the electronic brainstorms as a “free high.”)

Meningitis is a catch-all term for swelling of the tissues surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Specific viruses, fungi, and injury can all cause the potentially fatal condition but one of the most frightening and lethal causes is bacterial infection. Bacterial meningitis, caused by a handful of bacteria (Haemophilis influenza type b (Hib) or Streptococcus pneumonia and Neisseria meningitides) can kill in within a day, is often incurable, and may leave survivors with amputated limbs, hearing loss or brain seizures. My father was relatively lucky. One of the more intractable causes of meningitis is Neisseria, a bacterium adept at spreading through populations gathering together for the first time: freshmen dorms, summer camps, day care, the military barracks. Some five to twenty percent of us carry Neisseria in our nose and throat and unwittingly spread it around to those we share a meal, or a drink or a kiss. Most of us won’t get sick. A few of us may die from the infection, even today.

My kids were born in the 1990s. By the time they toddled off to school, they had received a slew of vaccines: measles, tetanus, mumps, polio, smallpox, chicken pox and even Haemophilus influenza and Streptococcus pneumonia (two other important causes of meningitis). But an effective vaccine against Neisseria meningitidis had not yet made it on to the recommended vaccine schedule. Then in 2005, just as they were heading off to the middle school milieu of new students, sweaty locker rooms, team sports and shared drinking bottles, a vaccine against a collection of N. meningitidis serotypes become available. Though the disease is rare here in the U.S.,compared to sub-Saharan Africa, in the so-called meningitis belt, I felt relieved. One more disease they wouldn’t get. Except.

Except for the escape artist, a serotype called meningitis B or MenB. Though rare, the infection that can take a turn for the worse within hours, has frustrated vaccine makers for decades. And it seems to pop up out of nowhere. In 2013 an outbreak at the University of California caused a freshman lacrosse player to undergo amputation of both feet. Four other students were infected, and the university was forced to provide prophylactic antibiotics to five hundred students. The next year an outbreak at that began at Princeton University caused the death of a Drexel student. In the first months of 2016, MenB hit three different colleges and killed one employee. Even in our “golden age of disease prevention,” and vaccine development, MenB has remained intractable through its ability to evade immunity.

It does this by wrapping itself in a sugary polysaccharide sheath that is identical to human polysaccharide molecules. Immune cells recognizing this molecule would have been naturally eliminated or deactivated as a protection against autoimmunity. By sequencing the pathogen’s genome vaccine makers have been able to discover antigenic proteins that would otherwise be hidden; four different antigens found on the majority of circulating Men B (a single pathogen may have several different circulating strains.) The discovery was a breakthrough for vaccine development. When Mariagrazia Pizza and co-workers reported their findings in the journal Science, they wrote: “In addition to proving the potential of the genomic approach, by identifying highly conserved proteins that induce bactericidal antibodies, we have provided candidates that will be the basis for clinical development of a vaccine against an important pathogen.” A few years ago when meningitis broke out at Princeton and UCSB campuses, the vaccine, licensed in Europe in 2013 but not yet here in the U.S., was offered to students on both campuses. One headline blared “California students to receive unlicensed meningitis vaccine.”

Sold as Bexsero by Novartis the vaccine (along with another new vaccine called Trumenba) was finally licensed in the U.S. in 2015. Hopefully it will become more widely available.

For more from CDC see here

This Valentine’s Day, we thought it would be fun for Island Press authors to share the love. We asked a few authors to choose their favorite Island Press book—other than their own, of course—and explain what makes it so special. Check out their responses below, and use code 4MAGICAL for 25% off and free shipping all of the books below, as well as books from participating authors.

What’s your favorite Island Press book? Share your answer in the comments.

My favorite IP book—not that I’ve read them all—is Mike Lydon’s Tactical Urbanism. This book shows how ad hoc interventions can improve the public realm, especially if they’re later made permanent. I discussed the concept on the latest Spokesmen podcast with architect Jason Fertig and illustrator Bekka “Bikeyface” Wright, both of Boston.

—Carlton Reid, Bike Boom and Roads Were Not Built for Cars

Last year I wrote a cover story for SIERRA magazine about how Donald Trump's proposed wall along the US-Mexico border would all but eliminate any chance for recovering jaguar species in the Southwest. In the course of my research I came across Alan Rabinowitz's An Indomitable Beast. It's a great read, blending Rabinowitz's own experiences as a big cat biologist with cutting-edge findings on this amazing species. As a writer, this book and its amazing details helped me bring the jaguar to life for readers.

—Jason Mark, Satellites in the High Country

This day is a time for reaching beyond data and logic to think about deeper ways of knowing. Love, specifically, but I would add to that faith, tradition and ethics. That's why I love Aaron Wolf's new book, The Spirit of Dialogue: Lessons from Faith Traditions in Transforming Conflict. Going beyond the mechanical "rationality" of the typical public meeting is necessary if we are to address the big issues of global sustainability and the smaller issues of how we sustain our local communities. Aaron Wolf provides the experience, tools and promise of a better, deeper approach.

—Larry Nielsen, Nature's Allies

Like many others, I am indebted to to Island Press for not one but three books that profoundly influenced my thinking. Panarchy (2001, edited by Lance Gunderson and C.S. Holling) introduced me to the concept of socio-ecological systems resilience. Resilience Thinking (2006, by Brian Walker and David Salt) taught me what systems resilience really means. And the follow-up book Resilience Practice (2012) helped me start to understand how systems resilience actually works. The latter remains the most-consulted book on my shelf—by Island Press or any other publisher—and I was thrilled and frankly humbled when Brian and David agreed to write a chapter for our own contribution to the field, The Community Resilience Reader (2017).

—Daniel Lerch, The Community Resilience Reader

"A large percentage of my urbanism bookshelf is comprised of Island Press books, so it's very difficult to share my love for just one! So, I won't because the books we pull of the shelf most often these days are the NACTO Design Guides. Finally, a near complete set of highly usable and mutually supportive design standards that help us advocate for and build better streets, better places."

—Mike Lydon, Tactical Urbanism

Nicols Fox's Against the Machine is a book that’s becomes more relevant each year as technology impinges ever further on our daily lives. It’s a fascinating, deeply researched look at how and why people have resisted being treated as extensions of machines.

—Phil Langdon, Within Walking Distance

Lake Effect by Nancy Nichols. I read this book several years ago. It is so important to hear the voices of those whose lives are impacted by industrial age pollutants, lest we slide into complacency. In this case, the story of the chemicals of Lake Michigan. It is a short, beautifully written, disturbing read.

—Emily Monosson, Natural Defense and Unnatural Selection

Peter Gleick’s series, The World’s Water, is one of the most useful surveys of the cutting edge of global waters there is. Each edition brings in-depth coverage of the issues of the day, always eminently readable and backed up by the crack research team that he puts together for each topic. I use it in my classes, always confident that students (and I) will be kept abreast of the best of The World’s Water.

—Aaron Wolf, The Spirit of Dialogue

Mark Jerome Walters' important book, Seven Modern Plagues, places great emphasis on linking emerging diseases with habitat destruction and other forms of modification natural processes. This book is a call for us to recognize that each new disease reflects an environmental warning.

—Andy Dyer, Chasing the Red Queen

My favorite Island Press book is The New Agrarianism: Land, Culture, and the Community of Life, edited by Eric T. Freyfogle. Perhaps it remains my favorite IP text because it is the first IP text I remember reading front to back, twice! I first encountered the book as a graduate student and was struck my its scope and tone. The book is thought provoking. But it's also a joy to read, which isn't surprising in hindsight given the award-winning contributors.

—Michael Carolan, No One Eats Alone

Don't see your Island Press fave? Share it in the comments below!

On the fourth of July, 1985, as the sun shone and the temperatures rose, people celebrated by eating watermelon. Then they got sick — becoming part of one of the nation’s largest episodes of foodborne illness caused by a pesticide. The outbreak began with a few upset stomachs in Oregon on July 3; by the next day, more than a dozen people in California were also doubling over with nausea, diarrhea, and stomach pain. A few suffered seizures.

All told, the CDC estimated that more than 1,000 individuals from Oregon, California, Arizona and other states, along with two Canadian provinces, became ill from eating melons, picked from a field in California, contaminated with a breakdown product of aldicarb — one of the most toxic pesticides on the market. There were the usual calls for the pesticide to be banned. While it was eventually scheduled to be phased out, now the chemical is back — albeit with more restrictions on its use.

Banning a pesticide is tricky business once it’s made its way onto the market and into fields and orchards. Consider the Environmental Protection Agency’s flip-flopping on a ban on the insecticide chlorpyrifos. In 2000, the EPA deemed chlorpyrifos too dangerous for home use, and allowances for food residues were reduced as well. Yet it remained popular — and legal — for agricultural use. In 2015 the agency concluded the chemical was too toxic to use on our fruits and vegetables. Then in 2017, the EPA flipped, granting the insecticide, introduced and widely sold by Dow Chemical, clemency. Finally, last Thursday, in a decision lauded by environmental groups, a federal court nullified the agency’s decision and ordered chlorpyrifos to be banned within the next two months.

In its ruling, the court did what the EPA wouldn’t, stating that there was no justification for maintaining “a tolerance for chlorpyrifos in the face of scientific evidence that its residue on food causes neurodevelopmental damage to children.”

For many, it’s hard to fathom why such a decision couldn’t have been reached years ago. After all, the EPA is directed to consider the costs and benefits of chemical use on the environment, and the potential health impacts on humans weigh heavily in the decision — particularly when establishing how much pesticide may remain in our food from fruit to grains, the exposure must be deemed “safe.” Though we might not recognize it, EPA regulations are currently responsible for protecting our daily safety in numerous ways. Every time we choose conventional foods over organic, for example, we are putting our trust in the agency’s decisions. Often, that trust is warranted. But recent advances in toxicology, the workhorse science of the EPA, suggest that regulations based on earlier testing may not protect consumers from harmful exposures.

Indeed, today’s toxicologists are finding adverse effects that their earlier counterparts could only have imagined. One striking recent discovery, for example, showed that pesticides and industrial contaminants can impact not only the individuals initially exposed, but also their offspring, grandoffspring, and possibly even great-grandoffspring. Another demonstrated how chemicals like bisphenol A — or BPA, used to make some plastics — causes subtle but irreversible damage to developing brains.

But changing regulations to reflect these new findings is complicated; as is evident from the corporate interests in chlorpyrifos, any new law has complex social, political, and economic impacts, making it a high stakes game. Chemical regulation and testing requirements simply can’t keep pace with science. Take for example, testing for chemicals like BPA. These so-called hormone-disrupting chemicals were known to be problematic since before the turn of this century, yet approved tests for these chemicals have only recently emerged.

Recognizing that standard toxicity tests may lag behind the science, the EPA reviews registered pesticides every 15 years or so, providing an opportunity to reconsider old chemicals in light of more recent data. New findings of toxicity can also prompt a review, which is what happened with the insecticide chlorpyrifos. A series of epidemiological studies suggested the chemical had adverse impacts on children’s brains, causing the Pesticides Action Network North America and the Natural Resources Defense Council to circulate a petition prompting an EPA review. In 2015, the agency determined that, based on the new science, chlorpyrifos was so toxic that no trace of the chemical should remain on fruits and vegetables — essentially an all-out ban.

Over the past few decades, multiple studies have shown that other chemicals known to be neurotoxic, like mercury and lead, can alter brain development and impact children’s behavior. As a result, acceptable thresholds for exposure to these chemicals have also been lowered. Previous toxicity tests on animals often failed to reveal these kinds of impacts, in part because, somewhat obviously, lab rats aren’t children. “We’re using behavioral paradigms that aren’t exactly the same,” Deborah Cory-Slechta, a neurotoxicologist at University of Rochester who studies both lab animals and humans, told me, “so they aren’t measuring the same thing [in animals] we are measuring in humans.”

Humans, in other words, are complicated: We eat odd foods, drink, take drugs, and stress out. All of these things can affect our response to toxic chemicals, yet none are included even in today’s animal testing. So it is not surprising that past chemical evaluations may have missed some critical toxic responses.

Chlorpyrifos is one of those chemicals for which traditional studies now appear to be insufficient. The insecticide kills the bugs it’s intended to deter by interfering with nerve signaling. Nerve cells constantly chatter with one another, sending chemical messages from nerve to nerve, or nerve to muscle. One such messenger is acetylcholine. Once a muscle cell, for example, is activated by acetylcholine it begins contracting. To stop the activity, the acetylcholine message must then be deactivated, much like the ringer on your phone turning offonce you answer so you can hear to talk. In this case, the enzyme acetylcholinesterase normally deactivates the messenger acetylcholine. But chlorpyrifos inhibits the enzyme, causing unabated signaling and potentially deadly overstimulation. (This is also how the lethal chemical warfare poison Novichok works.)

Toxicologists and regulators can measure the chemical’s effect on signaling to evaluate the impact of exposure to it. The EPA has used these results, along with other information, like when and how a chemical is used, to set food tolerances. Concentrations that don’t cause signaling inhibition, have historically been considered safe.

But part of the problem with setting these kinds of tolerances is that not everyone is affected equally. Studies over the last several decades suggest that infants and children — who have developing brains, maturing metabolic systems, and tend to eat a higher proportion of fruits and vegetables — may be more sensitive to some chemicals than adults. The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 addressed some of these concerns directing regulators to set standards for children’s health, and to consider the effects of cumulative chemical exposures. These include the additive effects of exposure to chlorpyrifos or similar pesticides, for example, by eating produce like peaches, snap peas, and bell peppers — crops that may be treated with the pesticide.

As the ability to study more subtle impacts of chemicals, particularly in the very young has improved, scientists began questioning if tolerances for chlorpyrifos should be reduced or eliminated because of its impacts on developing brains. “Growing cells are more vulnerable to toxins, and the brain forms over a longer period than do other organs,” wrote Bruce Lanphear, an epidemiologist at Simon Fraser University, in a 2015 paper published in the Annual Review of Public Health. Lanphear argued that to continue to regulate all chemicals as if they have a safe level no longer makes sense, particularly when it comes to protecting children from chemicals that impact brain development. We were taught that “low levels are of no consequence,” says Lanphear, “and we now know that’s not true.”

Chemicals that affect children’s brains, unlike those that injure organs like livers or hearts, affect not just our bodies but who we are, and early deficits are difficult to regain, unless there are serious interventions, says Cory-Slechta. Studies both in the laboratory and in children exposed in utero, suggested that the most recent restrictions on chlorpyrifos were not strict enough. One series of studies by Columbia University perinatal epidemiologist Virginia Rauh and her colleagues revealed an association between chlorpyrifos and intelligence and memorydeficits. The researchers used MRI imaging to find structural changes linked to exposure in the children’s brains. Some of those effects were found at concentrations below those causing acetylcholinesterase inhibition. These studies were just a few of those that convinced EPA regulators in 2015 that chlorpyrifos residues on fruits and vegetables could no longer be considered acceptable.

And then there was a national presidential election, and a new head administrator, Scott Pruitt, was appointed to the EPA. Bedeviled by scandal, Pruitt was forced to resign this summer, but not before postponing a decision on chlorpyrifos regulations until 2022, citing a return to “sound science,” emphasizing uncertainty and trading on doubt. Prior to the agency’s turn-around, former administrator Pruitt met with the CEO of Dow Chemical, which produces chlorpyrifos. Earlier in the year the company had donated $1 million dollars to President Trump’s inaugural activities and spent a total $13.6 million lobbying in 2016.

In May of this year, the state of Hawaii decided not to wait for the EPA, and banned chlorpyrifos. California also began taking another look. Then, this month in a case brought by the original petitioners along with a number of labor groups, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, citing the EPA’s failure to determine that exposures through food were safe and the agency’s “patent evasion” of it duties, ordered the agency to do its job and ban the pesticide.

Chemical regulation combines toxicology and other sciences with economics and politics. This is always a tricky process. But our health, and the health of the next generation, require an agency that is receptive to the best available science incorporating new insights into toxic chemicals and values health over profit. Toxicology has certainly advanced, but the federal body responsible for its application, the EPA, currently appears to be in retreat. Pruitt’s departure provides a modicum of hope, as do the federal courts — for now. But, should the agency continue to turn its back on its citizens — and its raison d’être — it will fall to the states, the courts and us, as concerned citizens, to step up.

This post was originally published at UnDark